(Guest post by A.D. Riddle.)

Since 1996, Kay Kohlmeyer has conducted excavations at the storm-god temple atop the citadel of Aleppo.

|

||

| Aleppo Storm-god Temple (Gonnella, Khayyata and Kohlmeyer 2005: 112). |

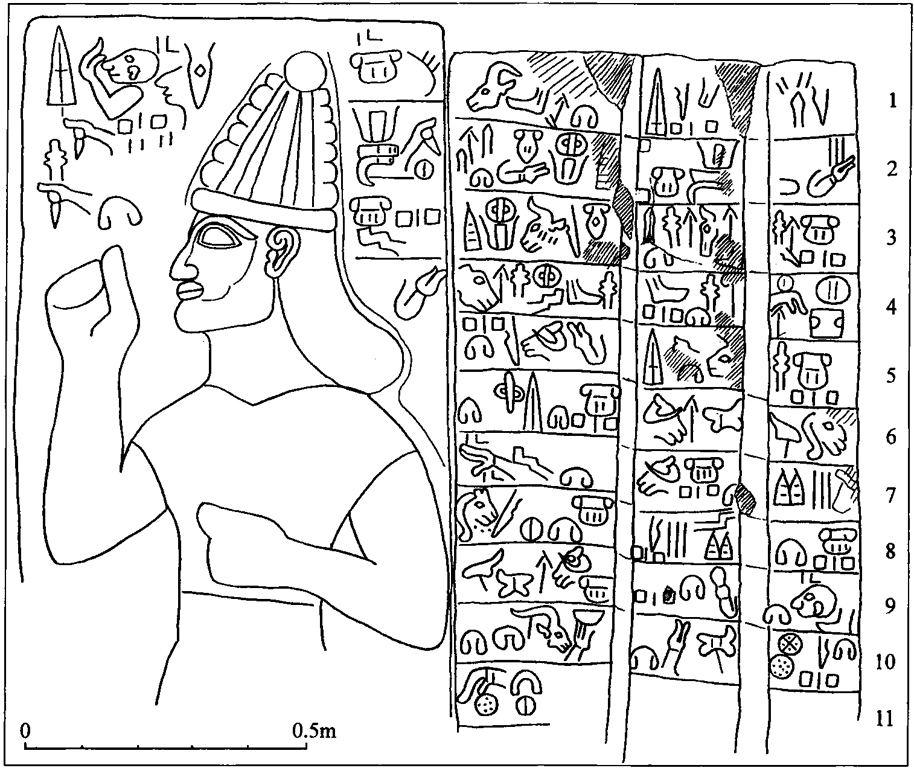

In 2003, a Hieroglyphic Luwian inscription was discovered in the temple which belonged to a king named Taita. We first mentioned the inscription last March. Now, full publication of the inscription by J. D. Hawkins has appeared in the latest issue of Anatolian Studies (vol. 61 [2011]: 35-54). The inscription is in the Hieroglyphic Luwian script and is designated ALEPPO 6 (there are other Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions from the temple, some also by Taita). The 11-line inscription is positioned behind a relief of Taita who faces the storm-god.

|

| Relief of Taita with Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscription (Kohlmeyer 2009: 198). |

The text of the inscription names Taita, the king of Palistin, and mentions his honoring the image of the storm-god of Aleppo. The majority of the inscription is given to ordering the kinds of offerings that should be brought, depending on whether (1) one is a king, prince, country-lord, or river-land lord, or (2) one is a lower-level ruler of some sort.

|

| Drawing of ALEPPO 6 (Hawkins 2011: 42). |

In our first post, there was a brief discussion of an article by Charles Steitler, in which he suggests identifying Taita with Toi/Tou, the king of Hamath mentioned in the Bible (2 Sam 8:9-11; 1 Chr. 18:9-11). At this time, there are three issues which make it hard to know for certain if Taita is Toi/Tou. First, it is hard to say why the additional -ta element at the end of Taita would have dropped off. Steitler identifies this element in other Hurrian personal names, but as far as I understand, it is not known for sure what it means, and if we do not know what it means, then we cannot explain why it would be lost. Second, Steitler suggests the shift in vowels from a to ō can be explained by the “Canaanite shift,” but this shift is thought to have taken place in the 14th century B.C., long before David, Toi/Tou, 2 Samuel or 1 Chronicles. (A friend has pointed me to an article by Joshua Fox [1996] which discusses a similar Phoenician vowel shift, but it is not clear to me how Phoenician would explain the change when moving from Luwian [or Hurrian] to Hebrew.) Third, Hawkins originally dated Taita to 900-700 B.C., and later adjusted this to sometime in the 11th and 10th centuries B.C., so pinning down the date is an issue for whether Taita could be Toi/Tou. But now, with the publication of ALEPPO 6, this last question concerning chronology has taken a new twist.

In the new article by Hawkins, he makes two modifications to his previous historical reconstruction.

First, he is more confident about dating Taita to ca. 1200 B.C. (11th century B.C.). This date is reached on the basis of (1) archaic features noted in the paleography of the ALEPPO 6 inscription, (2) radiocarbon dating of the storm-god temple phase associated with Taita, and (3) stylistic comparison of the sculptures from the Taita phase of the storm-god temple with the sculptures at the temple of ‘Ain Dara. Second, the archaic features in the ALEPPO 6 inscription indicate it is earlier than the other Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions connected with Taita which were found at Shaizar and Muhradah (about 13 miles northwest of Hamah, Syria). Hawkins suggests the possibility of two kings named Taita: Taita I and Taita II. But because the inscriptions of Aleppo, Shaizar, and Muhradah share many similarities—Taita’s name and title, and unique epigraphic features—Hawkins believes that Taita I and Taita II were separated by perhaps not more than a single generation, with Taita II possibly being the grandson of Taita I. Thus, Taita I who was responsible for the Aleppo inscription would have ruled in the 11th century B.C., and Taita II would have ruled in the early 10th century B.C.

It will be interesting to see how the historical picture continues to change as more information is obtained from excavations and studies, and then, what light this might shed on the time of David and our understanding of biblical history.

Image sources

Gonnella, Julia; Wahid Khayyata; and Kay Kohlmeyer.

2005 Die Zitadelle von Aleppo und der Tempel des Wettergottes: Neue Forschungen und Entdeckungen. Münster: Rhema.

Hawkins, J. D.

2011 “The inscriptions of the Aleppo temple.” Anatolian Studies 61: 35-54.

Kohlmeyer, Kay.

2009 “The Temple of the Storm God in Aleppo during the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages.” Near Eastern Archaeology 74/4: 190-202.

3 thoughts on “King Taita’s Inscription at Aleppo”

It's worth noting that offerings differ according to rank or status just like in the priestly code of Leviticus where the sin offerings are also differentiated by status (anointed priest, whole congregation, ruler and ordinary person, Lev. 4). This argues for an early dating of this material over against the late dating of much scholarship. Also, what is the background of the PN Palastin? This seems remarkably close to Philistine/Palestine.

Larry Helyer

Larry Helyer,

Thank you for the interesting observation about the differentiation of offerings. How useful, though, do you think such things are for dating texts?

Palastin is a fairly new reading of the name. It was only first suggested in print (as far as I know) in the 2009 issue of Near Eastern Archaeology. Before, the name was read Padasatin, but recent studies (say, in the last 3-4 years) in Hieroglyphic Luwian have suggested that the ta5 sign should be read lá and that the sà sign represents just s before another consonant: thus, Padasatin becomes Palastin. Hawkins is convinced of this new reading. While some scholars have already suggested a connection with the Philistines, I do not think it is a closed-case just yet. Ongoing excavations and new inscriptions are filling out our historical understanding of this area, so I would wait until we know more before drawing such conclusions. There are still a lot of things we do not know about this area during the early Iron Age.

A.D.

With regard to the dating issue, I deliberately used the word "material" and not text. The most that could be argued for is the relative antiquity of the traditions now incorporated into the text, which, of course, could be much later.

Thanks for the further discussion of the fascinating Palastin.

L. Helyer