|

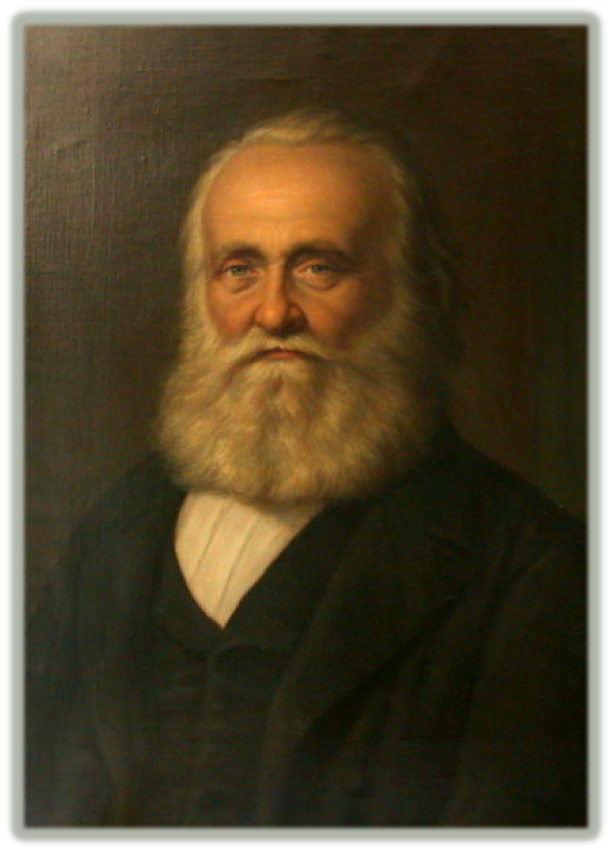

| From Konrad Furrer’s biography on Tobler |

Known affectionately as the “Father of German Exploration in Palestine,”[1] Titus Tobler (1806-1877), Swiss doctor and 19th century Palestine explorer, was an important figure during the mid-19th century explorations of the Holy Land.

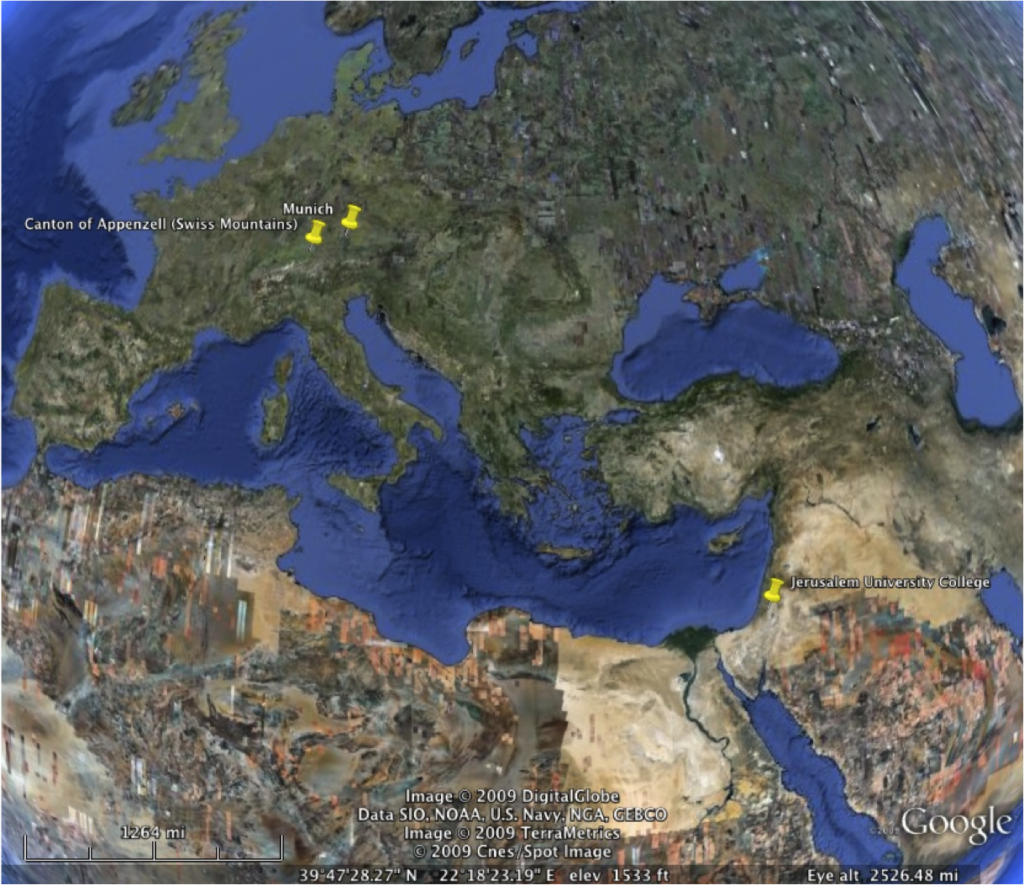

Over the course of his career Tobler made four expeditions to the Holy Land (1835, 1845, 1857, and 1865) – these expeditions were mostly directed at Jerusalem and its environs. Tobler came to Palestine the first time as a 29 year-old physician who had just begun to practice medicine in the mountains of Canton of Appenzell [2] Ten years later, Dr. Tobler returned to the Holy Land and accomplished one of the most in-depth, analytical studies of the region of Judea up until that time. This expedition had such a positive impact in mid-19th century scholarship that Tobler is considered by historians to be the most important explorer of Jerusalem in the 1840s.[3] Tobler’s personage and career are thought to be on par with the renowned Edward Robinson by researchers of the 19th century explorers of Palestine.[4] Tobler was a highly respected explorer and diligently worked on publishing his explorations and translating ancient pilgrim documents up until his death in 1877.[5]

Methodological Developments

Titus Tobler’s Holy Land expeditions and subsequent publications were contemporaneous with other better-known 19th century explorers such as the aforementioned Edward Robinson and the Survey of Western Palestine’s C.R. Conder and H.H. Kitchener. At first Tobler was dejected at the seemingly overcrowded group of scholars surveying, analyzing, and excavating the Levant in the 19th century. Despite this, Tobler was able to find his own niche within the broader framework of ancient Levantine studies by combining his own considerable knowledge and research with the concepts and publications of his contemporaries.[6] Tobler was one of the first to realize that there was no lack of problems to solve in Levantine research. Tobler concerned himself with more than the general scope of biblical studies and site identification – he began to study “the customs and manners of the people, the nature of the soil and climate, and many other things.”[7] In examining and categorizing these subjects Tobler introduced two scholarly tools into the Holy Land studies: the monograph and the bibliography.[8]

Wilson’s Arch – The 19th century explorer is most well known for discovering and suggesting the function of an arch from the Herodian Temple Mount to the Western Hill of Jerusalem. Today this arch is known as “Wilson’s Arch” after Charles Wilson who published it, but Wilson would not have known about the arch unless Tobler had showed it to him.[9]

The “First Wall” inside of Bishop Gobat’s School (modern day Jerusalem University College) – Tobler correctly identified the remains of Josephus’ “First Wall”[10] that runs along the rocky cliffs of the southwestern part of the Western Hill above the Hinnom Valley.

|

| The First Wall runs beneath the Bishop Gobat School (today’s Jerusalem University College) structure and continues through the Protestant Cemetery (to the right of the school – east) |

Quotes pertaining to Titus Tobler

Ben-Arieh shows Tobler’s perspective of other scholars as he quotes Tobler as saying, “Rivalry between explorers increases knowledge.”[11]

Tobler’s methodology and work ethic was summed up by Johannes Nepomuk Sepp (1816-1909)[13] as follows:

Additional Info:

For a complete list of Tobler’s 62 publications concerning Palestine refer to: Stern, S. and Haim, Goren. “A Bibliography.” Cathedra 48 (1988): 46-48.

See here for an English translation of Tobler’s bibliography of ancient Holy Land travelers (Appendix III – pages 391-411)

Check out one of Tobler’s maps of Jerusalem from Hebrew University’s database.

@font-face {

font-family: “Courier New”;

}@font-face {

font-family: “Wingdings”;

}@font-face {

font-family: “Cambria”;

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 10pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoFootnoteText, li.MsoFootnoteText, div.MsoFootnoteText { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }span.MsoFootnoteReference { vertical-align: super; }p.MsoListParagraph, li.MsoListParagraph, div.MsoListParagraph { margin: 0in 0in 10pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast { margin: 0in 0in 10pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }span.FootnoteTextChar { font-family: “Times New Roman”; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }ol { margin-bottom: 0in; }ul { margin-bottom: 0in; }