(Guest post by A.D. Riddle)

In addition to taking a trip to Israel or attending a class, museums are another excellent way to learn about the world of the Bible, but sometimes you do not always know what to look for or how to connect it to the Bible.

a class, museums are another excellent way to learn about the world of the Bible, but sometimes you do not always know what to look for or how to connect it to the Bible.

Clyde Fant and Mitchell Reddish, noted before on this blog for their guidebook to biblical sites in Turkey and Greece, have produced a book (a few years ago) that will help with just that:

Clyde E. Fant and Mitchell G. Reddish, Lost Treasures of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008).

The subtitle of the book is more informative: “Understanding the Bible through Archaeological Artifacts in World Museums.” The book’s contents are divided into eight sections that correspond to historical periods or to types of biblical literature.

Creation and Flood Stories

Israel’s Ancestral, Exodus, and Settlement Periods

The Period of the Monarchy

The Period of the Babylonian Exile

Poetry and Wisdom Literature

The Persian Period

The Hellenistic Period

The Roman Period

Two additional sections cover “Ancient Biblical Texts” and “Sensational Finds: Genuine or Forgery?”

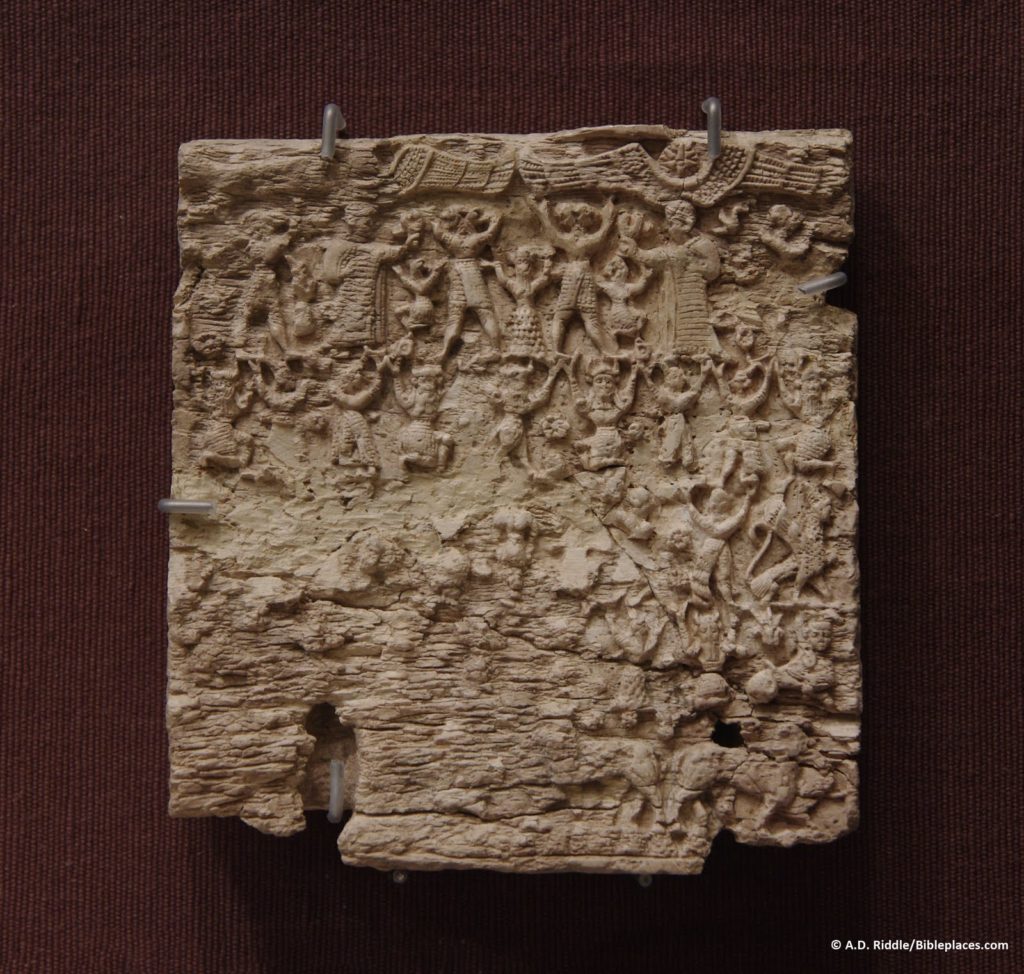

The richest sections are “The Period of the Monarchy” and “The Roman Period.” Within these ten sections, the book contains 107 entries, with some entries covering a single museum object and other entries covering a group of related objects. Each entry is about four-five pages in length and nearly all of the entries include a black-and-white photograph of the museum object. Entries begin with a description of the object(s): dimensions, language (if inscribed), provenance, date, museum location and number. This is followed by a prose description of the discovery of the object and its historical context. The authors provide a satisfying amount of detail in this section and it seems to be well-researched. The final section for each entry discusses the “Biblical Significance” of the object. Some objects, of course, have a more direct biblical connection than others, but others will draw your attention to details of the Bible that maybe you have not noticed before. Where the biblical significance is (or has been) disputed by scholars, Fant and Reddish present the options in a fair-handed way. For example, it used to be argued that the creation account in Genesis directly depended on Mesopotamian creation accounts, but Fant and Reddish are careful to point out both the comparisons and the contrasts.

The book includes objects from about 30 museums in the U.S., Britain, Germany, France, Israel, Turkey, Greece, and elsewhere. The book is made even more useful by including a scripture index, an index of museum numbers, and an index of objects organized by museum. So, for example, say you are going to visit the Oriental Institute Museum in Chicago, you can look up the museum in the index and see a list of objects on display so that you have an idea of where you might want to concentrate your attention while you are there. Or, say you are studying Acts and want to show how Luke was quite accurate and precise in many of the details he gives, you can use the scripture index to look up relevant entries.

There are, of course, many more objects and other museums that could have been included, but Fant and Reddish give good coverage of the most important objects (and many less familiar ones) and the most important areas of connection with the Bible. I think you will be pleased and impressed with the level of detail and the quality of research.