What’s surprising about this statement is not as much what it says as who said it. You’re free to guess in the comments below or make any observations. I’ll include the author and title of the book in tomorrow’s roundup.

It may be sufficient to remind you that nearly every scholarly “breakthrough” which has helped to bring about a revolution in Biblical studies has been the direct result of archaeological discoveries, whether accidental finds or the products of deliberate excavations. The new materials which have brought about a new understanding of the Bible have come out of the ground—and barring a direct descent of the Holy Spirit, it is hard to see how there could be any other source of new information. Take for example the recovery of the cuneiform literature of Mesopotamia over the last hundred years, which has given us parallel accounts of the Creation and Deluge; which has illuminated the whole era of the Patriarchs; which has provided a radically new understanding of Israelite law; which has filled in the background of the period of the Assyrian and Babylonian destructions; which for the first time in modern Biblical studies has fixed the chronology of many Biblical events. Or we may note the recovery of the Egyptian records, which has thrown such light on the period of the Patriarchs, the Amarna Age, the Exodus and Conquest, and most recently in the Nag Hammadi manuscripts has promised a revolution in New Testament and Early Patristic studies in some way comparable to that occasioned by the discovery of the Qumran scrolls a few years ago. From Anatolia the recovery of the Hittite literature has rescued from obscurity a people known to us previously only from the Bible.

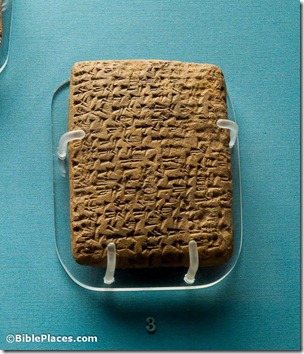

Amarna Letter from Yapahu of Gezer (EA 299),

Amarna Letter from Yapahu of Gezer (EA 299),

now on display in the British Museum

32 thoughts on “Who Said This?: Archaeology and New Understandings of the Bible”

It's Bill Dever! In "Archaeology and Biblical Studies:

Retrospects and Prospects". http://books.google.com/books?id=1vAgAAAAMAAJ&q=It+may+be+sufficient+to+remind+you+that+nearly+every+scholarly+%E2%80%9Cbreakthrough%E2%80%9D+which+has+helped+to+bring+about+a+revolution+in+Biblical+studies+has+bee&dq=It+may+be+sufficient+to+remind+you+that+nearly+every+scholarly+%E2%80%9Cbreakthrough%E2%80%9D+which+has+helped+to+bring+about+a+revolution+in+Biblical+studies+has+bee&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ngdfUfWLDoblyQGOgoGgCQ&ved=0CC4Q6AEwAA

For a newbie to archeology…why is this surprising?

From one who has followed the debate for some years- I'm not sure. Perhaps it is this sentence:

"Or we may note the recovery of the Egyptian records, which has thrown such light on the period of the Patriarchs, the Amarna Age, the Exodus and Conquest, and most recently in the Nag Hammadi manuscripts has promised a revolution in New Testament and Early Patristic studies in some way comparable to that occasioned by the discovery of the Qumran scrolls a few years ago.".

-Dever no longer accepts the historicity of the Patriarchs, Exodus, or Conquest. But we already knew that Bill Dever was the son of a fundamentalist preacher whose faith was destroyed by the solid rock of scholarship:

http://books.google.com/books?id=Lc_R1E1wD9cC&pg=PA335&dq=william+dever+fundamentalist&hl=en&sa=X&ei=9UNfUfeCJefzygGFvYH4Cg&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=william%20dever%20fundamentalist&f=false

and that there was no serious opposition to the Albrightian paradigm before the year Dever wrote this passage:

http://books.google.com/books?id=lwrzapZYqFAC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22de+Gruyter,+1974%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=AUVfUdWIHqWMygH3_IHYCw&ved=0CF0Q6AEwCTgK#v=onepage&q=%22de%20Gruyter%2C%201974%22&f=false

, so I don't see why this is surprising.

Pithom – thanks for the links. I don't know if you're serious about the "solid rock of scholarship," but either way, it's the biggest joke I've heard in a long time. If there's anything uncertain in this world, it's the assured results of critical scholarship. One's confidence in it increases the further one moves from it.

Gale – Dever led the charge against "biblical archaeology." Yet here, in a book published in 1974, he is affirming much of what he would later decry.

I had no intention of humor with my use of the phrase "solid rock of scholarship". I largely meant archaeological scholarship, not higher criticism.

I have spent much of the last year reading archaeological reports of sites in northern Israel. There is very little that I would consider "rock solid." There are higher and lower degrees of probability. And there is a lot of circular reasoning. It is truly astonishing.

@Todd Bolen

Can you give some examples? Which reports are you reading?

This is a complicated subject that requires much more than can be communicated in a blog comment (or that I'm willing to devote time to now). I'm giving you my conclusion after significant research: there are few certainties in archaeological research. The more specific one gets, the less certain matters are. You can talk to other people in the field and see if they have a similar opinion or not.

One quote comes to mind that reflects a similar opinion:

Amihai Mazar: "The interpretation of archaeological data and its association to the biblical text is a veritable minefield, as it is often inspired by the scholar's personal attitude towards the text…we face over and over again arguments that, at their core, are circular. This was as true at the time of William F. Albright and his followers as it is today. There are few items of data in the archaeological record that are not disputable."

Source: “The Spade and the Text: The Interaction between Archaeology and Israelite History Relating to the Tenth–Ninth Centuries BCE.” In Understanding the History of Ancient Israel, ed. H. G. M. Williamson, 145. Oxford: Oxford University Press for The British Academy, 2007.

Ah yes, the "solid rock of scholarship" that in days gone by assured us that LMLK seals dated to the Hebrew conquest, no later than King Saul's reign; & in recent days has given us a graduate student reading the clear, crisp letters of "MMST" on a freshly excavated handle bearing the word "Socoh". As recently as last year we even saw Dr. Israel Finkelstein, editor of a prestigious peer-review journal, informing us in print that people with PhD's occasionally commit "honest oversight" in their work. I'm with Todd on this one. And "For ever, o LORD, Thy Word is settled in Heaven."

@G.M. Grena

-That was before Tel Batash, Lachish, or any Edomite site had been excavated. Thus, there was no sound pottery chronology available to those who wished to date the lmlk impressions.

-That was an off-the-cuff attempted reading before the handle had been washed by a graduate student who didn't realize the handle was upside-down. It was not published in a single scholarly paper.

-There is no doubt honest oversight is often committed in the scholarly community.

Dear pithom, truly "solid" rocks don't need exceptions like the 3 you listed to qualify their solidity. Scholarship is the product of fallible human reasoning based on extremely limited information. Only a foolish mind would consider it "solid", especially mainstream modern scholarship that doesn't acknowledge the Holy Bible as containing a revelation from God.

@ G.M. Grena

Even solid rock can be cut by copper and sand.

http://books.google.com/books?id=oLDuHvQODoIC&pg=PR16&dq=%22A+tubular+hole+in+diorite%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=uclgUcjDOZTxrAH2soCwAw&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22A%20tubular%20hole%20in%20diorite%22&f=false

Besides, the off-the-cuff reading wasn't even scholarship. I can find no genuine "revelation from God" in the Bible.

"[S]solid rock can be cut…"

Equivocation fallacy. You would not have used the phrase "solid rock of scholarship" if your intention was to convey something that could be sliced, diced, eroded, & crumbled into dust capable of being blown by the slightest breeze.

"[T]he off-the-cuff reading wasn't even scholarship."

Would you have labeled it "scholarship" if he had used his advanced schooling to read it correctly? Answer: Yes. Circular Reasoning fallacy. You're arguing that scholarship is a solid rock, because scholars are always right; therefore if it's wrong, it's not even scholarship. If I've misrepresented your position, give us some examples of scholarship that's wrong/misleading/useless, & explain how this is characteristic of solidness.

"I can find no genuine 'revelation from God' in the Bible."

I believe you. "The fool hath said in his heart, 'There is no God'" (Psalms 14:1, 53:1). End of discussion as far as I'm concerned.

Interesting conversation my little question sparked. Thanks all for your contributions, and some great links.

This issue of Biblical inerrancy has been something I've been struggling with lately. I am not a scholar and don't have the background to defend either position…but have come to this position myself which may change with time: If some small section of the Bible were proven untrue that would not mean I would have to throw out my faith in the whole book. I know that when police look at eye-witness testimony, that if the stories match up completely, that if there are no differences in the story, that is a sign of it being concocted, not of it being true. So maybe if there are, say, slight differences in the gospel acounts…that could be evidence of their veracity, not their falsehood. Grand falsehoods (mis-quoting of Jesus' teachings, concocting mericles he didn't do, ect.") would have been challenged by contemporaries. People of that time would have challenged it–as we see false teachings being corrected by some of the new testament letters. But inconsequential things (like order of events) may not have been as likely to have been corrected. In other words, I think I can accept the possibility that there might be minor errors in some of the Biblical writings without having to toss out my whole faith and religion. All that is apart from any argument as to whether there actually IS error in the Bible.

Ok, I welcome you all to tear my un-academic ideas to shreds. I learn from that.

@ G.M. Grena

"Equivocation fallacy"

-You're right in this case. I should not have used that analogy. My intention was to say that scholarship could be reshaped by evidence, though clearly I did not get that intention across. Don't put words in my mouth. I would have said "no" until the reading was formally published in a scholarly journal. I did not say that scholarship was always right. Rather, some scholarship (e.g., that which argued Jericho and Ai were destroyed in the 13th century BC, Lachish III was destroyed in 597 BC, and Beitin showed good evidence of occupation in the Achaemenid period) has come to incorrect conclusions. The fact the conclusions of this scholarship were discarded in the 1970s and 1980s shows that the scholarly community can correct its past mistakes, unlike the fundamentalist Christian community, which stubbornly refuses to correct the mistakes of the authors of a collection of ancient texts. Thus, the rock of scholarship looks more solid than that of fundamentalist Christianity.

Though some fools may say there is no God, not all those who say there is no God are fools.

Gale,

Sometimes reading texts is a little more complex than whether or not there are no errors, small errors, or something else. You first have to learn "how" to read a particular text. I am talking about genre. For example, does a road atlas contain errors if it depicts a blue highway with red outline (when in reality highways are some color of gray, often with white and yellow dashed or solid stripes)? No, because you know how to read the atlas, and you know that the colors encode information other than the actual color of the highway. We would conclude that anyone who thought the atlas was misleading because of the highway color was in fact misreading the atlas. In ancient texts, certain types of language are used for different purposes, and a competent reader is familiar with these conventions and expectations so that they do not misread the text. For example, in summary statements found in historiographic materials, there might be hyperbole (overstatement). This might seem misleading to us, and some might claim it is an error, but hyperbole is frequently found in ancient Near Eastern texts of this type, and ancient readers would expect it and know how to "read" it.

Also, it may be that many "errors" are attributable to the fact that we do not possess enough information about the actual events (thus, the "solid rock" of scholarship shifts, undergoes modification, or sometimes is completely overturned). Neither ancient texts nor archaeology give us a complete record of the past so we have to be cautious about labeling something an error.

A.D.

@Gale

-So far as I know, people don't rise from the dead, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and inconsistencies in major matters do not seem to concern the religious. Why do people still believe Ron Wyatt's blood claims when the Standishes debunked them over a dozen years ago (and pointed out major inconsistencies in them)? It is a mystery to me. It is also a mystery why anyone would believe that a crucified man came back to life after having died.

Pithom,

You might find the book Miracles: The Credibility of the New Testament Accounts, by Craig S. Keener (Baker, 2012) to be of interest. Your plausibility structures have been shaped by your experience, but you must know that your experience (or lack thereof) is not shared by most people in most cultures throughout history, including many people who come from "modern, scientific" cultures.

A.D.

I agree with J. I. Packer that the real surprise (or difficulty, if you will) is not the resurrection but the incarnation. Here are a few quotes from Knowing God, chapter 5. I recommend it all, but can only include a portion.

"The real difficulty, because the supreme mystery with which the gospel confronts us, does not lie here [in the miracles] at all. It lies, not in the Good Friday message of atonement, nor in the Easter message of resurrection, but in the Christmas message of incarnation. The really staggering Christian claim is that Jesus of Nazareth was God made man – that the second person of the Godhead became the ‘second man’ (I Cor. 15:47), determining human destiny, the second representative head of the race, and that He took humanity without loss of deity, so that Jesus of Nazareth was as truly and fully divine as He was human….

This is the real stumbling-block in Christianity. It is here that Jews, Moslems, Unitarians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and many of those who feel the difficulties above-mentioned (about the virgin birth, miracles, the atonement, and the resurrection), have come to grief. It is from misbelief, or at least inadequate belief about the incarnation that difficulties at other points in the gospel story usually spring. But once the incarnation is grasped as a reality, these other difficulties dissolve….

But if Jesus was the same person as the eternal Word, the Father’s agent in creation, ‘through whom also he made the worlds’ (Heb. 1:2, RV), it is no wonder if fresh acts of creative power marked His coming into this world, and His life in it, and His exit from it. It is not strange that he, the author of life, should rise from the dead. If He was truly God the Son, it is much more startling that he should die than that He should rise again."

Gale,

Jesus said that not one jot or tittle (the smallest letter and stroke of the pen) will disappear until everything is accomplished (Matt 5:18). He believed that even the smallest detail was true.

Paul said that all Scripture is inspired by God (2 Tim 3:16).

Once you permit the possibility of errors, you become the judge of Scripture, determining what is from God (and therefore true) and what is not. In 20 years of graduate study and teaching, I have not found any reason to believe that there are any errors in the original manuscripts of the Bible. I don’t claim to understand everything, but I find it preferable to affirm the truth of God’s Word instead of picking and choosing according to my own limited knowledge. I encourage your study in this area and can recommend a book or two if you're interested.

Hey, Todd,

This is getting pretty far from your original post, but I've got to ask you for clarification about this:

"In 20 years of graduate study and teaching, I have not found any reason to believe that there are any errors in the original manuscripts of the Bible. I don’t claim to understand everything, but I find it preferable to affirm the truth of God’s Word instead of picking and choosing according to my own limited knowledge."

So…theoretically, couldn't you file *any* difficulty under the rubric of "I don't understand"? Even if there were a case of what seems to be a clear contradiction – e.g., where one text says A and another says non-A – you could just respond with "I don't understand this, but I know that both of these texts are correct." In other words, you could just suspend judgment on that particular issue – no matter what it is – while still affirming inerrancy. So here's my question: if this is the case, then how would you ever know if you're wrong about inerrancy?

Danny – thanks for the question. I don't think this is an issue that is up for debate every time I read the Bible. I'm not always "litigating" this issue in my mind. I've studied it carefully in the past and come to a conclusion with a high degree of confidence. So as I come across difficulties today, I am measuring them against that high degree of confidence in my previous conclusion. A matter which may be resolved with a simple explanation or a textual corruption is not going to affect my conclusion. Some difficulties (but not many) are going to be categorized as "waiting for more information." As far as whether something theoretically could overturn my conclusion, I'd rather wait until that's not a hypothetical. Since I've studied this a great deal and see very little that's new any more, I don't feel any hesitation in moving forward with my conclusion.

I find this statement by Nigel M. de S. Cameron to be helpful in my thinking:

"Every challenge to infallibility must carry sufficient weight to overthrow the whole principle of Biblical authority, or it must fall." (Cited in Walter Kaiser, Toward Rediscovering the Old Testament, p. 72).

Thanks, Todd. I certainly understand the idea of our views having momentum based on previous experience. They should; it would be impossible to function in daily life if this weren't the case. Still, I think you'd agree that the most rational approach is to let new information update our beliefs, so that we're *always* litigating and questioning or modifying our prior conclusions. To refuse to do this would essentially be saying that our conclusions trump reality – that we'll believe them no matter what new evidence we encounter.

You said:

"As far as whether something theoretically could overturn my conclusion, I'd rather wait until that's not a hypothetical."

I don't understand what you mean here. Wait until *what's* not a hypothetical?

@A. D. Riddle

"Your plausibility structures have been shaped by your experience, but you must know that your experience (or lack thereof) is not shared by most people in most cultures throughout history, including many people who come from "modern, scientific" cultures."

-There's a place on this planet where people used to rise from the dead all the time? Tell me more! I speak with sarcasm.

Danny – I agree that we are always learning, and learning means allowing new ideas to shape and change our thinking. Most of my learning builds on previous study; I'm not re-laying a foundation every day, week, or year.

Replace "that's not a hypothetical" with "that situation is not a hypothetical situation."

Sorry, Todd, I'm still not sure that I understand you on the hypothetical situation (which was your response to my original question). Do you mean that if you came across a discrepancy in the text, that you'd rather wait until you find information that resolves the discrepancy instead of concluding that there is an error of some kind in the text? I'm pressing you because I really want to understand how this is all filed away in your brain.

Danny – I'm not sure how to say it any better, at least in a blog comment. In any case, I suspect that any question trying to understand my brain will be better answered in conversation. I hope that won't be too long.

I hope so, too.

ALL revolutions in biblical thought have archaeological catalysts?

I would argue that most revolutionary idea was the documentary hypothesis (JEDP) that developed in the 19th century. As far as I know, this had nothing to do with archaeology; rather, it was careful textual study that made it clear that one author (Moses) was not responsible for the pentateuch.

The erosion of easy confidence in biblical authority caused by this was the catalyst for the 19th century's "biblical archaeologists" who wanted to prove the bible's correctness in the face of significant doubts raised by textual analysis.

@Feiker

-You're right. I wonder why I didn't notice that before.

Pithom,

Not sure about "all the time," but I assume you think resurrection never happens. See Keener pp. 536-579.

A.D.