(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

This week we focus our attention on the site of the first excavation in Palestine. When and where did this event take place? According to Neil Asher Silberman in his fascinating book Digging for God and Country, the year was 1810 and the site was Ashkelon.

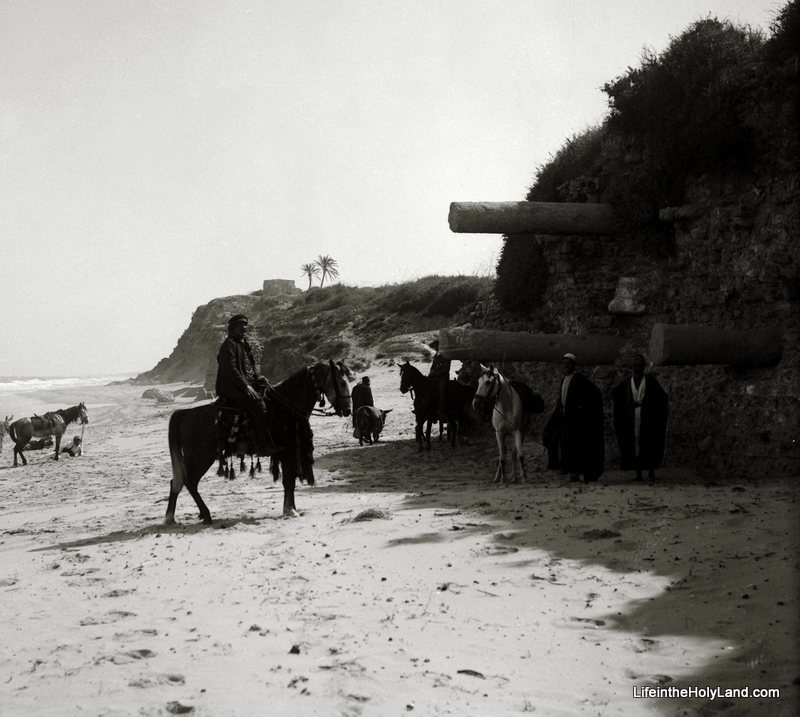

We actually have two pictures this week: one is from Volume 4 of the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands, and the other is from Volume 3 of The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection. The first image is how this site looked around 1910 or 1920 (a hundred years after the first excavation) and the second image is how the site looked in 2001 (almost two hundred years after the first excavation).

Both pictures were taken from almost the exact same spot. Notice the same set of columns protruding from the cliff in each picture. (Apparently the horses were unavailable for the photo op in 2001.)

On pages 24 to 27 of Digging for God and Coutnry, Silberman tells the fascinating story of an eccentric woman named Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope. She came from a prominent family in England and so was a lady with some means. She attempted to put that wealth to good use by pursuing exploration in the Middle East.

After a daring visit to Palmyra in 1810, she received a copy of “an intriguing ancient document” from some Franciscan monks which “described a fantastic treasure of gold bullion said to have been secretly buried in the ruins of the ancient city of Ashkelon on the Mediterranean coast, giving precise details of its location.” After getting further proof from the monks that the document was authentic, she reached out to the British government to help her retrieve the treasure, but (unsurprisingly) she was turned down. The story continues…

Sending word of her intentions directly to the sultan in Constantinople, Lady Hester began the journey down the coast to Ashkelon…. Arriving at the ruins of the Philistine city, Lady Hester settled into a comfortable cottage in a nearby village and conscripted hundreds of local fellahin to begin the work of excavation. The treasure map indicated that the gold was buried beneath a ruined mosque, and it was there that the digging began.

At the end of the fourth day of excavation, several huge pillars were discovered lying side by side as if to conceal a secret hiding place. The sultan’s representative hastily summoned special winches and ropes, but as the huge stone cylinders were lifted and removed, it became clear that the treasure they concealed was of neither silver nor gold.

It was the huge headless statue of a Roman emperor—the first archaeological artifact ever discovered by excavation in Palestine.

But beneath the statue was nothing, and Lady Hester was seeking gold, not classical art.

Ordering the statue to be set upright—and out of the way—she ordered the workers to resume digging for the treasure at another part of the site.

After several more weeks of excavation, a maze of empty trenches and haphazard piles of overturned earth testified grimly to the fruitlessness of the search…. Rather than admit to herself that the treasure map was a hoax, she became convinced that the late al-Jazzar had himself removed the treasure only a few years before. All that was left to her was the Roman statue.

Lady Hester was determined to demonstrate, however, that unlike other British antiquarians she had no interest in filling a museum; her search had been undertaken unselfishly, with regard only for the friendship of the Ottoman ruler. She had seen for herself the aftereffects of Lord Elgin’s removal of the Parthenon frieze while in Athens several years before, and she did not want her excavations to encourage similar plundering in the Holy Land. With a wave of her hand, she ordered the workers to destroy the monumental statue and cast its fragments into the sea.

With that act, Lady Hester Stanhope ended her brief but memorable archaeological career….

Wow. How times change. There’s a lot we could say about that first excavation, but I will content myself by saying that fortunately the current excavations are being carried out much more responsibly. But if you would like a piece of the first artifact ever excavated in Palestine, allow me to suggest a walk along the beach at Ashkelon looking for fragments of a Roman statue discovered (and destroyed) in 1810.

These photos and hundreds more are available in Volume 4 of the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands and Volume 3 of The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection. The former volume is $39 and is available here; the latter volume is $20 and is available here (both include free shipping within the U.S.). Additional photos and information about Ashkelon can be found here on the BiblePlaces website. The excerpts were taken from Neil Asher Silberman, Digging for God and Country: Exploration, Archaeology, and the Secret Struggle for the Holy Land, 1799-1917 (New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1982), pp. 24–26, and is available for purchase here.