Archaeologist Shimon Gibson has proposed in a recent lecture that the visible destruction of the Temple Mount walls occurred not in AD 70 with the Roman conquest of Jerusalem but instead during a massive earthquake in AD 363. From Haaretz (premium):

“Now we know much more about the late Roman period,” Gibson says. “If there was a neighborhood like this there, how could it be that they leave debris from the year 70 C.E. in the middle of it all? It’s like going out of your house and leaving a pile of debris. You clear it. And why leave the city to bring stones to build new buildings if you have stones next to your house?”

Next to the heaps of destruction, Mazar’s granddaughter, Eilat Mazar, uncovered a Roman-era bakery. “Who would buy bread in a place with damaged walls above it and fallen stones?” Gibson adds. “You don’t build next to a four-story ruin.”

You might, especially if those ruins were particularly large and difficult to move. There may also have been some Roman motivation to leave the ruin as a monument to what happens to those who rebel against Rome.

Furthermore, Gibson argues that the Temple Mount architecture was imitated by later religious structures.

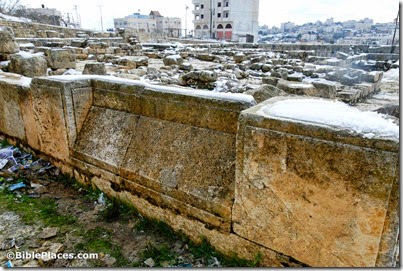

Gibson, a British-born archaeologist living in Israel, also points to the similarity in artisanship – comparing supporting pillars or other pillars that adorned the Temple Mount with the artisanship of those at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Tomb of the Patriarchs and Mamre (near Hebron).

The three sites contain religiously important structures, which were built hundreds of years after the destruction. According to Gibson, the builders of these structures, at the beginning of the fourth century C.E., saw the Temple Mount walls and tried to imitate them, as part of the effort of Christianity at that time to prove that it was the successor of Judaism.

If the walls were destroyed in 70 C.E., asserts Gibson, how could the builders of 325 C.E. succeed in copying them, considering the fact that they did not have access to archaeological drawings or photographs? He concludes that the walls still stood hundreds of years after the destruction, and served as inspiration for the Roman builders.

Typically the structures of Mamre and the Machpelah in Hebron are dated to the time of Herod, not later, thus accounting for the similarity in design.

Photos from the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands

Ronny Reich excavated the material that Gibson is now questioning. Not surprisingly, he does not agree.

“It doesn’t hold water,” he states. Reich’s strongest evidence against the theory is a layer of mud or dirt several centimeters thick, which was discovered underneath the fallen stones.

‘The rockslide doesn’t lie on the street. It lies on a layer of sediment 3-5 centimeters thick,” he says. “We cleaned this layer very exactingly, and we found 120-125 coins. It is sediment that collected on the street after it went out of use and before the collapse – I suppose in the first winters after the destruction. The last coin we found is from the fourth year of the rebellion, that is to say 69 C.E. If Gibson is right, could it be that for 290 years, no other coins were collected under the pile of stones? What happened between 70 and 363?”

Read the full article by Nir Hasson here.

I’d like to see more of the discussion between these archaeologists, but at this point, I don’t think the textbooks need to be rewritten.