Visitors to the Garden Tomb of Jerusalem are usually shown the “Skull” identified by Charles Gordon as part of the case that this spot may be the authentic site of Jesus’ crucifixion and burial. On February 20 the bridge of the skull’s nose collapsed during a storm. Our friend Austen Dutton visited the site, alerted us to the event, and sent us this photo.

For contrast, here’s a photo taken in 2008.

Visitors to the Garden Tomb are shown the passage that identifies the place of Jesus’ death as “the place of the Skull.”

“Carrying his own cross, he went out to the place of the Skull (which in Aramaic is called Golgotha)” (John 19:17).

It is worth noting that the Gospels never explain why the place was identified by a skull, nor does it say anything about a hill. The name could have come from a geological feature that bore this resemblance. Or it could have been for another reason altogether.

The recent storm and the resultant erosion suggests that the escarpment would have been greatly altered in the years since it was created by quarrying. I would consider it doubtful that anything like the skull-shape visible in recent years was known in the first century. Fortunately for those who prefer the Garden Tomb location, this has never been the primary support for its identification.

Our Jerusalem volume in the American Colony and Eric Matson Collection has a section devoted to the Garden Tomb. In notes written by Tom Powers, he provides some of the fascinating background to the identification of the skull.

General Charles Gordon, spending several months in Jerusalem in 1883, became firmly convinced that the hill seen here was the Golgotha of the New Testament. The idea of Skull Hill as Golgotha was not original with him, however, as several earlier travelers and writers had proposed the same identification beginning as early as the 1840s, and Gordon certainly knew of some of these. Among the other proponents of this view was Claude Conder, a Palestine Exploration Fund explorer and surveyor who was sent to Palestine in 1872 and recorded the idea in two of his books, Tent Work in Palestine (1878) and The City of Jerusalem (1909).

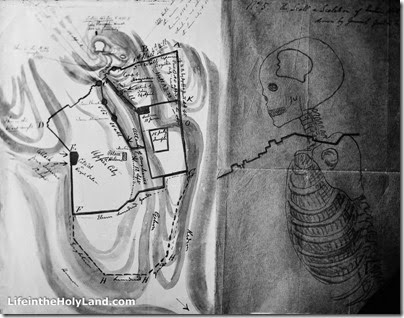

Gordon, however, added his own unique, mystical notions to the theory, however, based in part on both topography and Biblical typology. He believed, for example, that because sacrificial animals were slaughtered in the ancient Jewish temples north of the altar, according to the Mishnah, that Jesus must have been crucified north of the city. Further, Gordon devised a conceptual scheme by which he superimposed a human skeleton on a map of Jerusalem. The skull, not surprisingly, fell on Skull Hill (and he even pinpointed the human figure’s esophagus, a known water channel that entered the city beneath the north wall)!

Gordon added at least one other unusual aspect to the Skull Hill speculations: Being a military man, he consulted a detailed map of the area, the Ordnance Survey Plan of Jerusalem, and was struck by a particular contour line—2549 feet (797 m) above sea level—which, encircling the summit of “Skull Hill,” formed what looked to him like the outline of a human skull. Mention is sometimes made, somewhat derisively, of a revelatory dream or vision that Gordon had, but this seems not to be mentioned in the general’s own writings nor in contemporary accounts.

Gordon expressed his views in a flurry of letters and reports sent to various acquaintances and colleagues, including many to Conrad Schick and many others to Sir John Cowell in England, comptroller to the royal household. General Gordon was a hugely popular figure in his day, the perfect embodiment, one might argue, of military heroics, fervent Christian faith, and Victorian Romanticism, and after his death in Khartoum in 1885 his stature and fame only grew, if that were possible. In any event, there is no denying that the force of his personality provided an important impetus toward the acquisition, development and promotion of the Garden Tomb site, and did much to cement its credentials in the popular imagination.

Bertha Spafford Vester, daughter of American Colony founders Horatio and Anna Spafford, recounts her childhood memories of the famous General Gordon (1882–83):

“Five is not too young for hero worship, and my hero was a frequent visitor to our house, General Charles George ‘Chinese’ Gordon, ‘the fabulous hero of the Sudan’. He was fulfilling a lifelong dream with a year’s furlough in Palestine, studying Biblical history and the antiquities of Jerusalem. This was the only peaceful time the general had known in many years, and it was to be his last. . . . The general lived in a rented house in the village of Ein Karim . . . and General Gordon came often from his village home to Jerusalem riding a white donkey. . . . Whenever General Gordon came to our house a chair was put out for him on our flat roof and he spent hours there, studying his Bible, meditating, planning. It was there that he conceived the idea that the hill opposite the north wall was in reality Golgotha, the ‘Place of the Skull’ . . . He gave Father a map and a sketch that he made, showing the hill as a man’s figure, with the skull as the cornerstone. Part of the scarp of the rock of what is known as Jeremiah’s Grotto made a perfect death’s-head, complete with eye-sockets, crushed nose, and gaping mouth. Ever since then this hill has been known as ‘Gordon’s Calvary,’ although archaeologists are skeptical on the subject . . . Father did not agree with all the general’s visionary ideas, but he liked to talk about these and many other subjects with him, and they were good friends. Mother wanted General Gordon to have peace when he was meditating on the roof, and cautioned me not to disturb him, but I would creep up the roof stairs and crouch behind a chimney; there I would wait. I watched him reading his Bible and lifting his eyes to study the hill, and my vigil was always rewarded, for at last he would call me and take me on his knee and tell me stories.” — Bertha Spafford Vester, Our Jerusalem: An American Family in the Holy City, 1881-1949 (Ariel, 1988), pp. 102-3.

Photos from The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection