By Chris McKinny

In the previous post – I indicated that I was cynical about the Cenacle being the location of Pentecost. For Part 1 – see here. In this post, we will look at some of the implied intertextual allusions related to Pentecost and the coming of the Spirit. In the last post, we also highlighted Lexham Geographic Commentary on the Book of Acts through Revelation. For this one – I’d like to highlight the excellent collection of photos and notes put together by the BiblePlaces team. The full entry is Anderson, Steven D., A. D. Riddle, Kris Udd, and Todd Bolen. Photo Companion to the Bible: Acts. BiblePlaces, 2019. This amazing resource is available on this site – click the above link or photo below. This current post utilizes many photos from the PCB Acts.

Continuation of excerpt from McKinny, Chris. “The Location of Pentecost and Geographical Implications in Acts 2.” Pages 77–93 in Lexham Geographic Commentary on the Book of Acts through Revelation. Edited by Barry J. Beitzel. Lexham Press, 2019.

We will now turn our attention to the numerous intertextual allusions between the Old Testament (and the Gospel of Luke) and Acts 2. [1] We will organize these possible allusions chronologically, but our intention is to show both the chronological and geographical development of the relationship between the Holy Spirit and God’s people with specific emphasis on the temple mount.[2]

The Reversal of Babel – Genesis 11:1-9; Acts 2:5-13

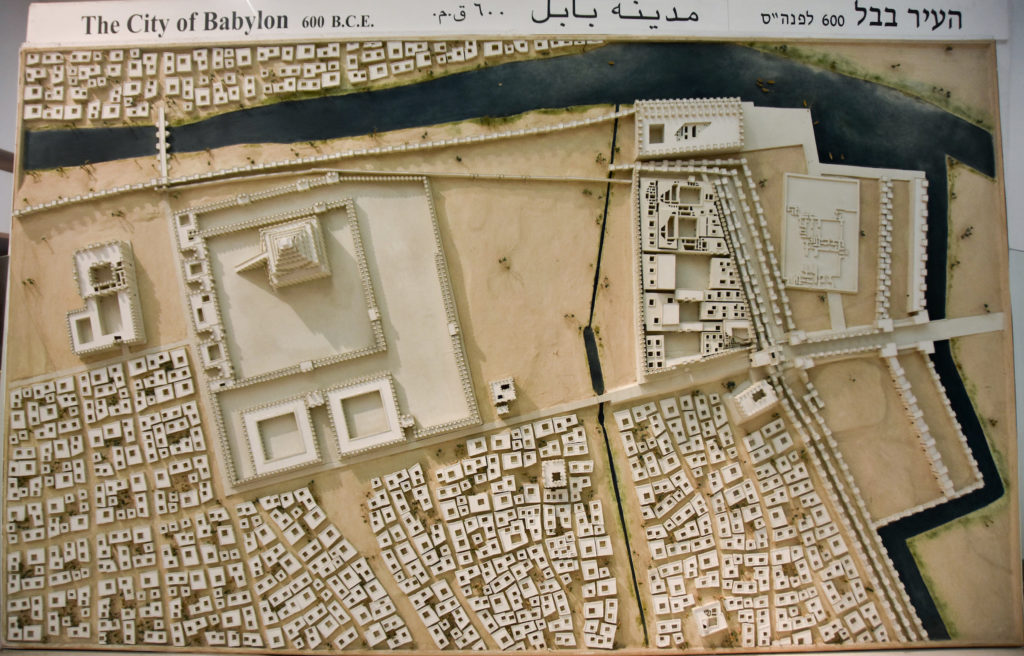

The first allusion to an Old Testament passage is rather obvious – the reversal of the confusion of languages at the tower of Babel (Gen 11:1-9) with the supernatural ability to understand foreign speech in their original language at Pentecost (Acts 2:5-13).[3]

- Compare the “whole world… moved eastward to the plain of Shinar and settled there” (Gen 11:1) to the gathering together of Jews from “every nation under heaven” (Acts 2:5).

- Compare the “whole earth had one language and the same words” (Gen 11:1) to “each one was hearing them (the disciples) speak in his own language” (Acts 2:6).

- Compare the confusion after the change of languages (Gen 11:7-9) to the “bewilderment” of understanding those hearing their own language come out of a Galilean mouth (Acts 2:6, 12).

- Compare the “plain of Shinar” and “Babel” (Gen 11:1, 9) to the first Jews mentioned in “Parthians, Medes, Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia” (Acts 2:9) who are clearly identified with Jews of the Babylonian diaspora.

- Compare the preceding table of nations in Genesis 10 (who are the subject of Gen 11:1-9) to the list of Jews from all over the known world in Acts 2:8-11.

- Compare the source of the language confusion in Genesis 11:5-8 (Yahweh)[4] to the source of the language understanding in Acts 2:11 (i.e., God, cf. also Acts 1:8)

Finally, the intertextual link between Babel and Pentecost points to the conclusion that the coming of the Holy Spirit would undo the division of peoples and their “scattering over all the earth” (Gen 11:8) by inaugurating a new era of “understanding” between the nations, even those who are “far off” (Acts 2:39; cf. also Acts 10:44-48). Moreover, it also implies that God was opening a new way to heaven for at least 3,000 (Acts 2:41) of the “devout men from every nation under heaven” (Acts 2:5), after the failed attempt at Babel to reach heaven by means of “brick, stone and mortar” (Gen 11:4). With regards to the three-fold geographical “outline” of the events of the Book of Acts (Acts 1:7 – Jerusalem/Judea, Samaria, and the end of the earth), the reversal of Babel at Pentecost is the first step in the process which will culminate in the apostle’s bringing the Gospel “to the ends of the earth.”

The Giving of the Law – Exodus 24:12-18; Acts 2:1-13

There are not explicit textual allusion between Pentecost (Acts 2) and the giving of the Law (Exod 24:12-18).[5] However, second temple Jewish literature plainly points to the fact that contemporary Jews believed that Pentecost was the day when the law was given at Sinai.[6] Specifically, it was understood that Moses was given a covenant that had already been given to Noah (“on heavenly tablets”), which had been lost until Sinai (Jub 6:15-23). Against this contemporary backdrop, parallels between the two events are relatively straightforward.

- Both events contain fiery theophanies (Exod 24:16-17/Acts 2:3-4, cf. also Christ’s “cloud” in Acts 1:9). Both events are connected with a new covenant (cf. Luke 22:20; Jer 31:31).

- Both events use a prophetic messenger to explain the significance of what God has done (Moses – e.g., Exod 25:1-2; Peter – Acts 2:14). Regarding this, VanderKam points to the possible echo of a rabbinic tradition in which all the foreign speakers heard the giving of the Law from Sinai in their 70 languages (b. Shabb. 88b).[7]

- Finally, one can also point to the subsequent spiritual anointing of the 70 elders at the tent of meeting in Numbers 11:25.[8] This event directly links the transfer of Yahweh’s Spirit from Moses to the elders at His place of residence (i.e., the tent of meeting). Moses’ following statement to Joshua in Numbers 11:29 indicates the hope that one day “all Yahweh’s people were prophets, that Yahweh would put His Spirit on them!” This text likely lies behind Joel 2:29,[9] and is therefore particularly relevant to the outpouring of the Spirit at Pentecost.

The “Cloud” of Yahweh in the Solomonic Temple – 1 Kings 8; Acts 2; cf. Acts 1:9

The next allusion is connected to an intertextual chain that can be traced back to the theophanies associated with Yahweh’s cloud seen at the giving of the Law (Exod 24:15-18), throughout the wilderness wanderings (e.g., Exod 13:21-22; Num 14:14), and his residence in the tent of meeting after its construction (Exod 33:9; Num 12:5; Deut 31:15). Significantly, the rest of my suggested allusions are geographically localized to the temple precinct as a result of Solomon building “the house of Yahweh” (1 Kgs 6 ) and, subsequently, Yahweh’s physical indwelling of his house (1 Kgs 8:10-13).

On this occasion (which is probably a parallel to the Feast of Tabernacles, cf. 1 Kgs 8:2), Solomon assembled all of the leaders of Israel and had the priests bring up the “ark of Yahweh, the tent of meeting, and all the of the holy vessels that were in the tent… to its place in the inner sanctuary of the house, in the Most Holy Place (i.e., the Holy of Holies), beneath the wings of the cherubim” (1 Kgs 8:4-6).[10] With his physical mobile throne and his treasures secured in his new residence, Yahweh appeared once more in his theophanic cloud that “filled the house of Yahweh, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud, for the glory of Yahweh filled the house of Yahweh” (1 Kgs 8:10-11). In my opinion, Solomon’s inauguration of Yahweh’s temple is clearly parallel to the events of Pentecost. Consider the following parallels:

- Both events feature the gathering of Israelites/Jews from everywhere (the kingdom/diaspora) to the temple in Jerusalem (1 Kgs 8:1; Acts 2:5).

- Both groups witnessed the astonishing, supernatural physical manifestation of God’s Spirit in the form of cloud (1 Kgs 8:10-13) and tongues of fire (Acts 2:1-5).

- Both events specifically reference the “house” being filled by Yahweh’s Spirit (1 Kgs 8:10; Acts 2:2). From my perspective, this intertextual link is one of the main reasons why the events of Pentecost should be located on the temple mount.[11]

- Both events were followed by the main leader (Solomon/Peter) delivering a long oration directed at explaining the significance of what the crowd had just seen (1 Kgs 8:12-61; Acts 2:14-40).

This last parallel requires some unpacking. For Solomon (1 Kgs 8:12-61), Yahweh’s presence in this new house meant the fulfillment of Solomon’s end of the Davidic covenant (2 Sam 7; cf. 8:12-26) and the perpetuation of the Mosiac covenant with its blessings and cursing (e.g., Deut 32-33, cf. 1 Kgs 8:31-61). Significantly, Solomon also expressed his humility and incredulity that the uncontainable Yahweh would graciously choose to reside in a permanent structure from which he would hear the “pleas of your servant (i.e., Solomon and Davidic kings) and of your people” (1 Kgs 8:27-30).

Likewise, Peter employed Joel 2:28-32 to explain the supernatural phenomenon that they had just observed – namely the outpouring of Yahweh’s Spirit (Joel 2:29) upon them. In its contemporary first temple setting (as well as Peter’s day), the prophecy of Joel is based on the basic understanding that Yahweh’s Spirit was not at that time upon individual people (except for unusual circumstances, e.g., Elisha – 2 Kgs 2), but resided in the inner sanctuary of the temple. Therefore, it stands to reason that Joel 2:28-32 is textually linked to 1 Kings 8 (as well as 2 Ch 5-6). Accordingly, the prophecy of Joel concerns a future event that will shift the localization of Yahweh’s Spirit from a physical structure to a spiritual people (cf. also Jer 3:15-18; Zech 12:10). Therefore, Peter was claiming that the prophecy of Joel was currently being fulfilled before their very eyes. In light of the connections that we have outlined above, Peter was also implicitly referencing the earlier indwelling of the Solomonic temple on which Joel’s prophecy is based. Peter, like Solomon, then explained that this amazing change had occurred on account of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus – the son of David (Acts 2:32-41; cf. Solomon’s use of the Davidic Covenant above). But he also makes the bombastic claim that Jesus received the “promise of the Holy Spirit” from the Father and was the one “who poured out this that you yourselves are seeing and hearing” (Acts 2:33). In this regard, Peter proclaimed that Jesus was responsible for the filling of Yahweh’s new temples (i.e., the disciples) with his Spirit, in the same way that Yahweh was responsible for filling his physical temple in the days of Solomon. To underscore this intertextual link, compare Jesus’ “cloud” that the disciples saw at his ascension a few days before the events of Pentecost (Acts 1:9).

The Departure of Yahweh’s Spirit from the Solomonic Temple – Ezekiel 8-11

In relation to what we have discussed above, it is worth mentioning that according to the prophetic visions of Ezekiel, Yahweh’s Spirit departed from the Solomonic temple in the years before its destruction (Ezek 8-11).[12] In this vision, the Spirit is personified as a mobile throne with “whirling wheels” (for details see Ezek 10:2, 9-17; cf. 1:5-21) and also as a “cloud with brightness around it and fire flashing forth continually” (Ezek 10:3; cf. 1:4). With regards to the latter description, the cloud is obviously linked with 1 Kings 8:10-13, and it seems probable that the fire (πυρὸς in the LXX) of Ezekiel 1:4 and 10:6 can be connected to the “tongues of fire (πυρὸς)” of Acts 2:3.[13]

Besides similar imagery between the depictions of Yahweh’s Spirit, Ezekiel’s multi-step departure of Yahweh’s glory/Spirit from the Solomonic temple in Ezekiel 10-11 can be linked to the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. First, before the departure of the Spirit, Ezekiel 11:19-20 indicates that a “new spirit” would be placed within the returning Israelites. This is a clear connection to Christ’s outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost (Acts 2:33). Second, Ezekiel’s address was to those who were “far off among the nations… those scattered among the nations” (Ezek 11:16), which mirrors the addressees of Peter’s sermon in Acts 2:39 (cf. Joel 2:32). Third, Jesus ascended from the same location that the Spirit had departed to – the Mount of Olives (Acts 1:12; Ezek 11:22; cf. also Zech 14:4). Therefore, Jesus’ outpouring of the Spirit at Pentecost is a geographical reversal of the Spirit’s departure in Ezekiel 8-11. This geographical reversal is all the more intriguing when one considers that after mirroring the path of the Spirit from the Mount of Olives (Jesus – Acts 1:7-11) to the temple courts (Acts 2:1-5), the Spirit entered the disciples instead of re-entering through the torn curtain of the holy of holies (Luke 23:45; Matt 27:51; Mark 15:38; cf. Heb 10:20), and thereby fulfilled the prediction of the prophets (e.g., Ezek 11:19-20).[14]

The Return of Yahweh’s Spirit in and from His Son – Luke 3:16; Acts 2:33

On a related point, there does not appear to be a clear reference to the return of Yahweh’s Spirit to Zerubbabel’s temple. In my view, there are a number of textual parallels between Ezra 3 and 1 Kings 6-8 and the parallel passage of 2 Chronicles 2-6 (e.g., the celebration of the Feast of Tabernacles – 1 Kgs 8:2; Ezra 3:4; receiving cedars from Tyre and Sidon via Joppa – 2 Chr 2:16; Ezra 3:7; etc.). These parallels likely indicate that Ezra’s presentation of the return to and rebuilding of the temple is attempting to follow in the steps of its glorious predecessor. However, these similarities stop abruptly with a huge difference at their conclusion. As we have seen, when Solomon inaugurated the temple (1 Kgs 8:1-12), Yahweh’s Spirit filled it and the people rejoiced. However, when the exiles finished inaugurating the temple – just at the point where one would expect to see the theophanic cloud return – nothing supernatural happened. In fact, Ezra 3:12-13 indicates that the “old men” who had seen Solomon’s temple wept over the sight of the new one. While it is obviously incorrect to state that Yahweh’s Spirit was not active during the second temple period, it seems significant that (to my knowledge) no reference is made to the return of Yahweh’s Spirit to its former home on Zion.

Against this backdrop, one should pay close attention to the Gospel predictions and depictions of Christ’s role in returning the Spirit both to its rightful home (i.e., the temple) and its new home (i.e., the hearts of his disciples). John the Baptist’s announcement of the Messiah who “will baptize you with Holy Spirit and fire” (Luke 3:16; cf. John 1:26) is a prediction that was fulfilled in Jesus’ outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost. Luke makes this clear within Peter’s appeal at the end of the sermon (Acts 2:38-40), which employs very similar language to Luke 3:16, 21-22. Therefore, in its main context within Luke-Acts, Pentecost serves as the fulfillment of Christ’s ultimate destiny that was promised by his forerunner. Still, one must also be attuned to the fact that the Gospel writers depicted Christ’s life and ministry as being “filled with the Spirit” following his baptism by John (e.g., Matt 4:1; Luke 4:1). As a logical inference, and even though this is never explicitly highlighted in the Gospels, one should not miss that Christ’s actions in the temple (e.g., Luke 4:9; cf. Luke 9:31) represented an actual physical return of God’s Spirit to his former residence. Nevertheless, Peter grounds his culminating argument in two great truths that are explicitly tied to location (or geography). First, the risen Jesus was currently seated at the right hand of the throne of God. Second, “this” Jesus had poured out the Holy Spirit in their midst (Acts 2:32-36).

Conclusion

In conclusion, and despite early Christian tradition to the contrary, the events of Pentecost should be entirely localized to the temple mount. This localization underscores numerous implied intertextual parallels between the appearances and activities of Yahweh’s Spirit from his residences (i.e., Sinai, tabernacle, and Jerusalem temple) and the outpouring of Yahweh/Jesus’ Spirit upon the disciples in Acts 2. The absence of the Holy Spirit from the temple following its departure (Ezek 11) and the prediction of Christ’s “baptism with the Holy Spirit and fire” (Luke 3:16) represent the major turning point in this geographical change from physical to spiritual. Notably, the anointing of the Holy Spirit upon the hearts of the followers of Jesus from Pentecost onward is one of the major pieces of Christ’s culminating redemptive work that supersedes the need for a physical, atoning temple with its various cultic protections and rituals (e.g., priests, curtains of separation, etc.) The transformation of the abode of the Spirit from a physical mountain, tent, or building, to a spiritual, sacerdotal people has massive implications for believers. This point is made clear by the temple imagery of Peter (1 Pet 2:9), John (Rev 1:6; 5:10; cf. “kingdom of priests” Exod 19:5-6), Paul (1 Cor 6:19), and the writer of Hebrews (especially Heb 9:6-22). Therefore, one can take immense joy when observing the geographical movements of the Holy Spirit that Peter (as recorded by Luke) described and implied during his Acts 2 sermon. In response, we might also, like Solomon did when witnessing Yahweh’s cloud filling “the whole house” (1 Kgs 8:27; Acts 2:2), marvel that our uncontainable God through the manifestation of his Spirit would choose to reside in his redeemed people, and thereby make them living, breathing temples of God (cf. 1 Pet 2:4-5).

[1] There are certainly more than I have discussed below, as my focus is primarily on the geographical implications associated with the intertextual allusions. For example, the reference to drunk priests and prophets in Isaiah 28:1-15 may be linked with Peter’s initial statement “these people are not drunk, as you suppose, since it is only the third hour of the day” Marshall, “Acts,” 531.

[2] When it comes to determining the viability of intertextual allusions or echoes, as a general guiding principle we should pay close attention to Paul’s instruction to the Corinthians (compare especially his association of Christ with “the spiritual Rock that followed them” 1 Cor 10:4). See discussion of method in A. Chou, The Hermeneutics of the Biblical Writers: Learning to Interpret Scripture from the Prophets and Apostles (Kregel Academic, 2018). With specific reference to Luke’s use of the Old Testament see B. Witherington III, The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Eerdmans, 1998), 123–27.

[3] Contra Marshall, “Acts,” 532 who does not see any “concrete evidence” for this connection.

[4] With the plural “us” in Genesis 11:7.

[5] James C. VanderKam, “Weeks, Feast Of,” Anchor Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 6.897.

[6] Marshall, “Acts,” 531.

[7] See discussion in VanderKam, “Weeks, Feast Of,” 6.897. B. Shabb. 88b reads as follows, “with regard to the revelation at Sinai, Rabbi Yoḥanan said: What is the meaning of that which is written: “The Lord gives the word; the women that proclaim the tidings are a great host” (Ps 68:12)? It means that each and every utterance that emerged from the mouth of the Almighty divided into seventy languages, a great host,” A. E. I. Stensaltz, “Shabbat 88b,” in William Davidson Talmud, Sefaria (Koren Publishers, 2017), https://www.sefaria.org/Shabbat.88b.3?lang=bi&with=all&lang2=en.

[8] “Yahweh came down in the cloud spoke to him (Moses), and took some of the Spirit that was on him and put it on the seventy elders” (Num 11:25).

[9] Marshall, “Acts,” 531.

[10] For the location of the Holy of Holies currently beneath the Dome of the Rock, see discussion in Ritmeyer, The Quest, 312–17.

[11] See discussion in Keener, Acts, 796–97.

[12] The return of Yahweh’s Spirit to the temple (from the Mount of Olives – “coming from the east”) is also predicted in Ezekiel 43:1-9, which is the reverse vision of Ezekiel 8-11 (cf. 43:3). Whether or not this was fulfilled or partially fulfilled at Pentecost is a matter of theological debate that goes beyond the scope of our discussion.

[13] Marshall, “Acts,” 531–32; see also D. L. Bock, Acts, 2 vols., Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament) (Baker, 2007) who in his discussion on Acts 2:2-3 connects Philo’s discussion of “fire” in Decalogue 11.46 and several Old Testament passages.

[14] A similar geographical connection can be seen in the use of Spirit/river imagery flowing from the the temple in Joel 3:18; Ezekiel 47:1-12; Zechariah 13:1; 14:8 which appear to be some of “the Scriptures” that Jesus was referring to in John 7:37-39.