In the inscriptions Taita is said to be the “Walastinean hero/king” or “Palastinean hero/king.” This title also appears in Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions found at Tell Tayinat, in the Amuq Plain in Turkey. It has been suggested that Tell Tayinat was the capital of Taita’s kingdom and that it extended east to Aleppo and south to Hamath. See most recently J. David Hawkins, “Cilicia, the Amuq, and Aleppo: New Light in a Dark Age,” Near Eastern Archaeology 72/4 (2009): 164-173.

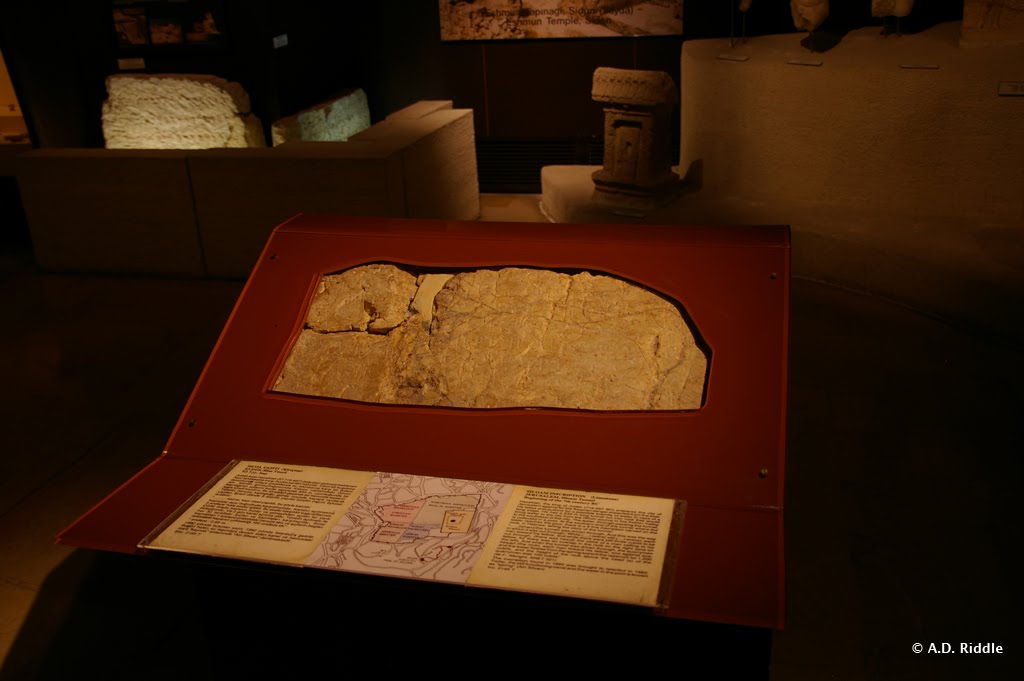

Fragment of a Hieroglyphic Luwian inscription from Tell Tayinat which mentions the “Walastinean king.” On display at the Oriental Institute Museum, Chicago.

Fragment of a Hieroglyphic Luwian inscription from Tell Tayinat which mentions the “Walastinean king.” On display at the Oriental Institute Museum, Chicago.

The Luwian language is closely related to Hittite, Lycian, and other Anatolian languages. Luwian was written in both a cuneiform script and a hieroglyphic script, no relation to Egyptian hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphic Luwian was used by kings of the Hittite Empire for monumental inscriptions and seals.

After the fall of the Hittite Empire, Hieroglyphic Luwian continued to be used in the Neo-Hittite and Aramean kingdoms that emerged. In publications, the inscriptions are often named after the place they were found. For the Late Bronze Luwian inscriptions from the Hittite Empire period, see this list. For the Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions from the Iron Age, see the three-part volume by John David Hawkins, Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2000), aka CHLI. It is reasonably priced at Amazon, though if anyone would like to make a contribution towards my purchase of the set, I am accepting offers. Inscriptions found since the publication of CHLI are listed here. Two years ago, I made a map showing the distribution of Iron Age Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions which can be viewed here. It is now outdated.

Returning to Taita, Charles Steitler recently published an article in which he proposed Taita is To‘î, a king who paid tribute to David after David defeated Hadadezer, king of Zobah (2 Sam 8:9-11; 1 Chr. 18:9-11). To‘î is a Hurrian name, and Steitler argues Taita is also a Hurrian name. There is a -ta element in Taita’s name which does not appear in the name To‘î. Steitler is not able to give a definitive explanation for the significance of this element, and thus, we cannot say why it would have dropped out. (Steitler’s article is entitled “The Biblical King Toi of Hamath and the Late Hittite State of ‘P/Walas(a)tin,’ ” Biblische Notizen 146 [2010]: 81-99. It was noted by several blogs beginning I think with Aren Maeir.) There is also the difficulty of dating Taita’s inscriptions. In CHLI, Hawkins said the dating of Taita’s inscriptions was doubtful, but suggested the period 900-700 B.C. In the 2009 article I mentioned previously above the photo, Hawkins now suggests a possible date between the 11th and 10th centuries B.C. So it is hard to know right now if Taita was King To‘î of the Bible.

Benjamin Sass has now written two pieces, one here and more recently, “Four Notes on Taita King of Palistin with an Excursus on King Solomon’s Empire,” Tel Aviv 37 (2010): 169–174. He suggests dating Taita to around 900 B.C. for the main reason that, for Sass, this paints a more satisfying historical picture.

Last month, Brian Janeway contributed a summary of these findings as well. It can be read here.

If these recent discussions are any indication, we can expect that Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions will more-and-more play a significant role in our reconstructions of the early Iron Ages. Kenneth Kitchen has already written a couple of essays in which he shows how these inscriptions are an important source of new information for understanding King David’s kingdom.

Kitchen, Kenneth A.

2002 “The Controlling Role of External Evidence in Assessing the Historical Status of the Israelite United Monarchy.” Pp. 111-130 in Windows into Old Testament History: Evidence, Argument and the Crisis of “Biblical Israel.” Ed. V. P. Long, D. W. Baker, and G. J. Wenham. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

2005 “The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of the Neo-Hittite States (c. 1200-700): A Fresh Source of Background to the Hebrew Bible.” Pp. 117-134 in The Old Testament in Its World: Papers Read at the Winter Meeting, January 2003 The Society for Old Testament Study and at the Joint Meeting, July 2003 The Society for Old Testament Study and Het Oudtestamentisch Werkgezelschap in Nederland en België. Ed. R. P. Gordon and J. C. de Moor. Leiden: Brill.

2010 “External Textual Sources — Neo-Hittite States.” Pp. 365-368 in The Book of Kings: Sources, Composition, Historiography and Reception. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 129. Ed. B. Halpern and A. Lemaire. Leiden: Brill.

And this is for that last reader who is not yet bored to tears. For more reading, probably the best place to start is Near Eastern Archaeology 72/4 (2009). The entire issue is dedicated to Taita, Tell Tayinat, and the Aleppo Storm-god temple. For more information on Luwians and the Luwian language, one might pursue:

Melchert, H. Craig, ed.

2003 The Luwians. Leiden: Brill.

Payne, Annick.

2010 Hieroglyphic Luwian: An Introduction with Original Texts. 2nd revised ed.Wiesbaden:

Harrassowitz.

UPDATE: I received today the latest issue of Biblical Archaeology Review. The cover story is an article by Victor Hurowitz in which he identifies similarities between the Aleppo Storm-god temple, two temples excavated at Tell Tayinat, and Solomon’s temple. See Victor Hurowitz, “Solomon’s Temple in Context,” Biblical Archaeology Review 37/2 (2011): 46-57 and 77-78.