As mentioned before, I took my first trip to Egypt this year. The main part of the trip was led by James Hoffmeier (Trinity International University) and was organized by Shepherd Travel. For those interested in traveling to Egypt, I am happy to recommend Shepherd Travel, and in particular, our guide Maged. At the end of the Hoffmeier trip, a friend and I remained a few extra days to visit additional sites. Maged was an enormous help during our extended time.

Egypt possesses many amazing places and artifacts to see, but travel in Egypt can present a few challenges. If we had not had Maged as our guide, it would have been extremely difficult (maybe impossible) to visit and photograph all the sites that we did.

Here are four ways having a good guide helped us:

Negotiation. First, everything in Egypt must be negotiated—from transportation, to prices and tips, to permission to enter some of the sites and permission to photograph. All of this takes time and knowledge of how things work (the ability to speak Arabic is also huge advantage). There were a few sites that were “closed” or where photography was forbidden, but Maged was able to negotiate our way into nearly every one of them. In addition, if we had been by ourselves, we surely would have paid more and tipped more (or less) than we needed to, because we are not familiar with the customs. Maged made sure we avoided these situations. (In Egypt, everything you can imagine requires a tip, and you have to be willing to give each transaction plenty of time to “transpire.” If you are in a hurry, you will probably miss out.)

Transportation. Second, we had to rely on local transportation. In other Middle East countries I have visited, it is not difficult to rent a car and do all of my own navigating, but I would not recommend this in Egypt. Instead, we utilized local drivers, trains, and subways for transportation. Some of this we could have figured out on our own, but it would have taken us twice as long and in some cases we probably would have paid (much) more than we should have. Maged arranged all our transportation needs to maximize our schedule and negotiated fair prices. In places where Maged was not with us, he made sure we had a driver, that the driver knew where we wanted to go, and that we knew how much we needed to pay and tip.

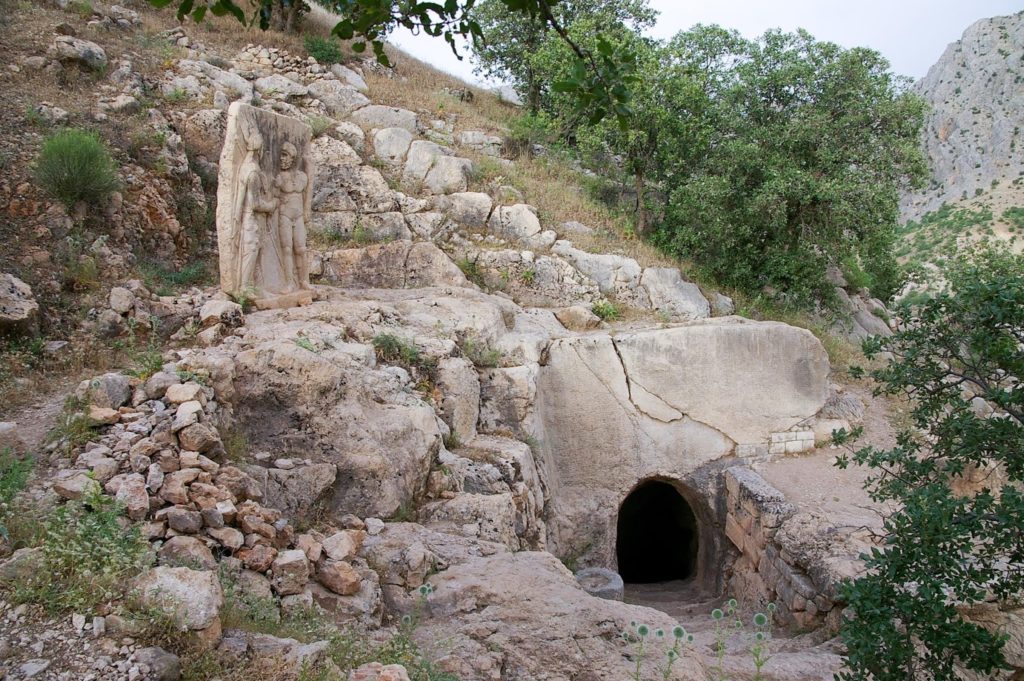

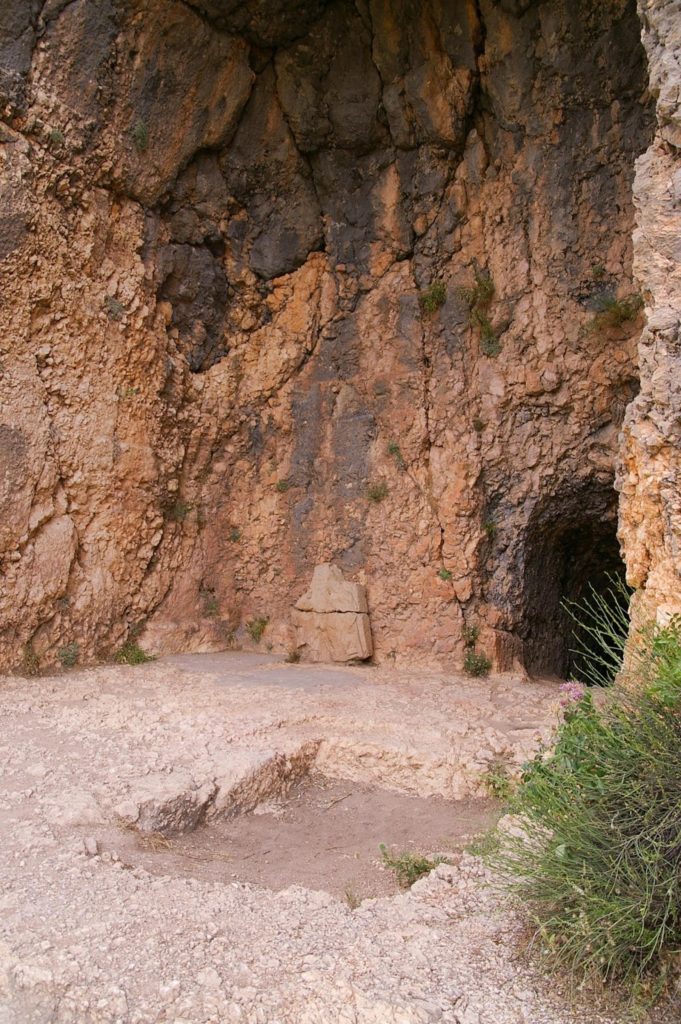

Security. Third, Egypt is very protective of tourists, excessively even at times. During the Hoffmeier trip, we noted at one site that the number of police and guards exceeded the 40-something members of our tour group. Travel to some sites and use of the desert highway require police escort, and it was helpful to have Maged explain our intentions to authorities, to procure their assistance when needed, and to keep us informed of everything that was going on. Maged also knew which sites are located in military zones and therefore off-limits, thus saving me wasted time and effort trying in vain to reach them. Finally, Maged could verify whether it was safe for us to travel to some of the out-of-the-way sites.

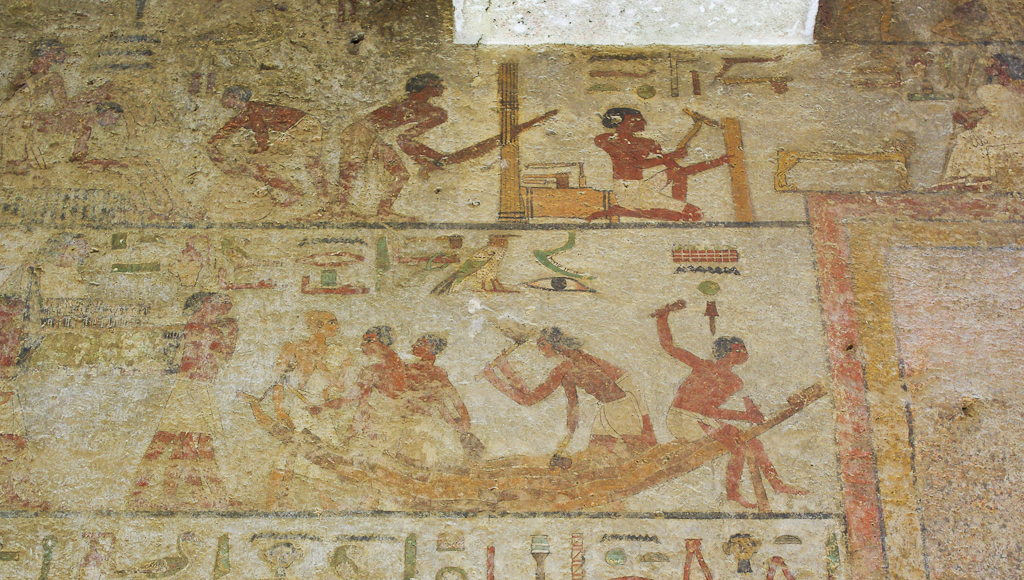

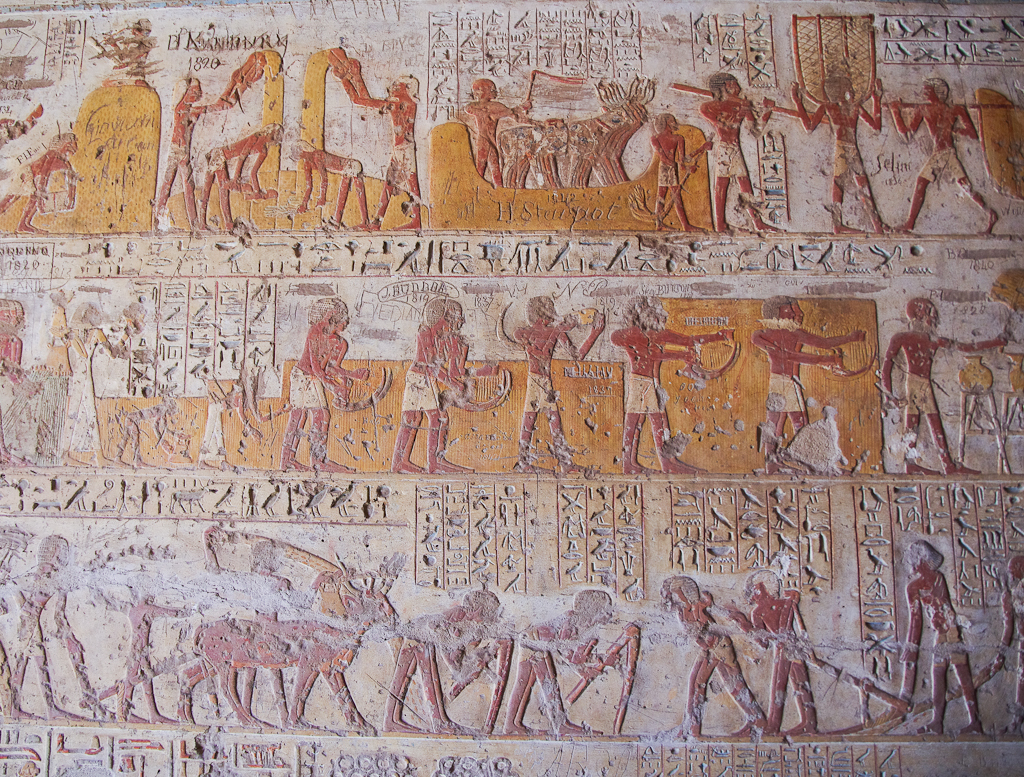

Expertise. Fourth, Maged studied Egyptian archaeology and ancient Egyptian language in university. He showed us his comprehensive exams in Egyptian hieroglyphs, hieratic and Coptic, and they looked quite impressive. He has participated in excavations and was familiar with all of the sites on my itinerary—even the ones that I thought were ultra-obscure. In addition, Maged is quite knowledgable about the history, sites, doctrines, and traditions of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Many American Christians probably are not too familiar with traditions related to Joseph and Mary’s flight to Egypt (Matt 2), the martyrdom of Mark in Alexandria, the ostensible fulfillments of Isaiah 19, the Desert Fathers, or the differences between the Latin and Eastern Church. And not least, Maged speaks very good English.

If you are thinking of taking a trip to Egypt, I recommend Shepherd Travel and ask for Maged to be your guide. You can find more at Shepherd Travel’s website or on Facebook.