The “Roads of Arabia” exhibition ends its U.S. tour on January 18, 2015, at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. The website does not indicate any further venues for the exhibition, so this might be the last chance to see it. Here are some of our posts about it on this blog (from most recent to earliest):

Roads of Arabia Volume in PDF (July 02, 2014) [The pdf is still available as far as we can tell]

Roads of Arabia Exhibition (June 24, 2014)

Roads of Arabia in Houston (January 08, 2014)

Roads of Arabia Exhibition: Update (April 23, 2013)

Museums and Cultural Heritage (April 05, 2011)

Archaeology of Saudi Arabia (February 27, 2011)

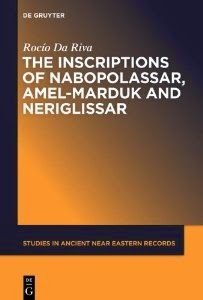

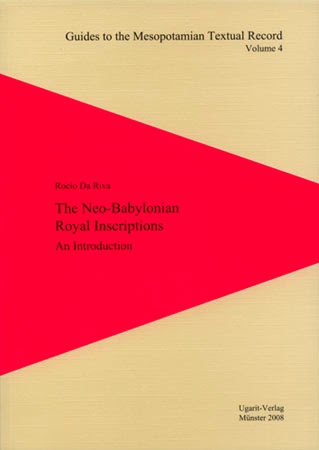

The official website of the “Roads of Arabia” exhibition is online here. I did not notice before that the site has a downloadable “Roads of Arabia Bibliography” at the bottom of this page (direct link). This looks like a helpful resource to have on hand. The first two items of the bibliography are exhibition catalogs. The first of these can be downloaded at the link given above. The second one looks very similar to the first catalog, but it is not exactly the same. Poking around online, I was able to locate a few of the individual chapters. These appear to have better quality images than the full-volume pdf.

- “Introduction: Roads of Arabia – Archaeological Treasures of Saudi Arabia”by Ali Al-Ghabban and Stefan Weber.

- “Natural Environment of the Arabian Peninsula” by Max Engel, Helmut Brückner, Karoline Meßenzehl.

- “Old Arabia in Historic Sources” by Daniel Thomas Potts.

- “Ancient Tayma’: an Oasis at the Interface Between Cultures New Research at a Key Location on the Caravan Road” by Arnulf Hausleiter [in German].

- “Dedan: Treasures of a Spectacular Culture” by Said Al-Said.

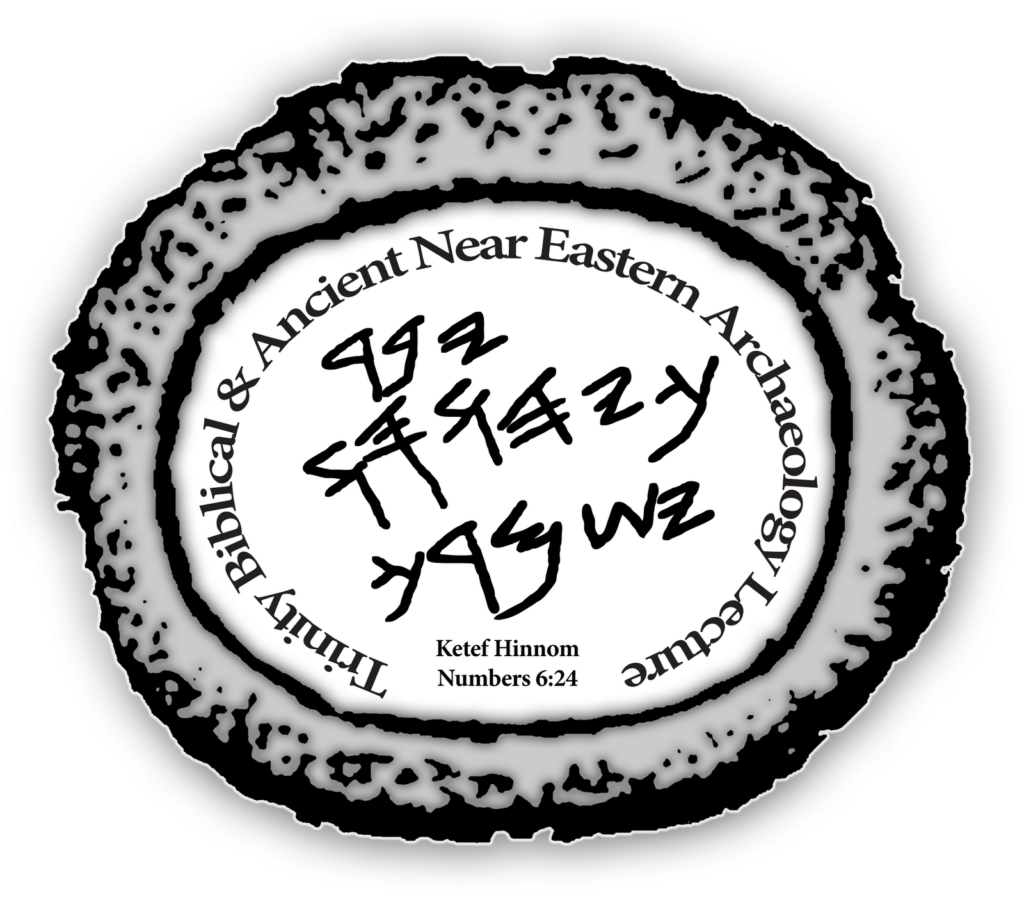

- “Writing Systems and Languages of Arabia – A Tour” by Michael Marx.