This series of posts examines the historical reliability of the New Testament books of Luke and Acts by comparing these books to other ancient textual sources and the archaeological record. Supplemental information of additional interest is often given as well.

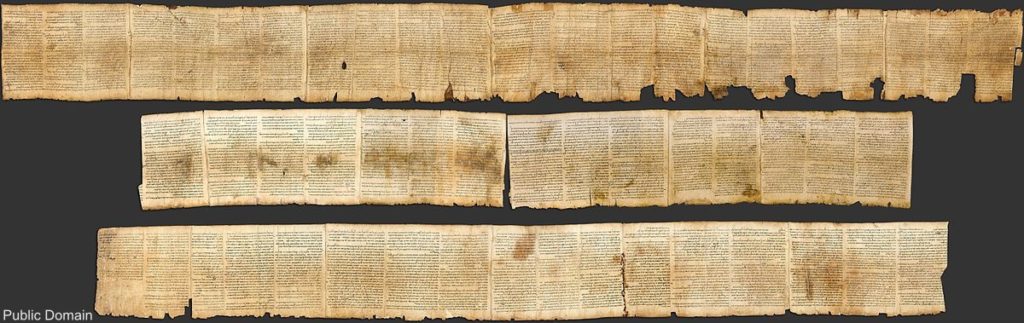

The text in Luke 3:3-6 speaks of the ministry of John the Baptist and makes reference to “the book of the words of Isaiah the prophet.” Interestingly enough, we now have an actual ancient copy of the book of Isaiah referred to by Luke, which, having been penned in ca. 125 BC, was written prior to the time Luke wrote his work. This ancient text, commonly called the Great Isaiah Scroll, is a well-preserved copy of the Old Testament book of Isaiah. Further, this same scroll is featured in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The entire scroll is shown in the following photo, which can be seen in more detail by clicking to enlarge.

Having been found in 1947, the Great Isaiah Scroll was one of the first of the Dead Sea Scrolls to be discovered, and—with the exception of some small damaged portions—it contains the entire text of the biblical book of Isaiah. Moreover, a handy digital version that scrolls electronically and has a translation app is now available to the public. This digital version is part of the larger Digital Dead Sea Scrolls collection.

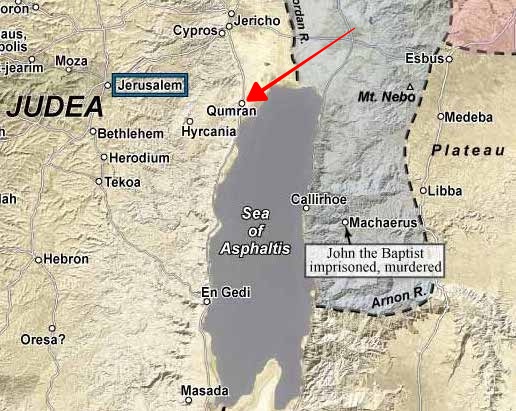

The Dead Sea Scrolls, which contain nearly all of the Old Testament books plus a number of other ancient works, were found in caves located in the hills around the ancient community of Qumran, which is designated by the red arrow on the following map cropped from the Satellite Bible Atlas.

The following photo shows a general view of the slopes west of Qumran where some of the caves are located.

The next photo shows the exterior of Cave 1 in which the Great Isaiah Scroll was found.

This final photo displays the interior of Cave 1 in which the first seven scrolls, including the Isaiah Scroll, were discovered.

Commonly thought to be written between 200 BC and AD 70 by a group of Essenes inhabiting the community of Qumran, the Dead Sea Scrolls, including the Great Isaiah Scroll, represent a simply unrivaled collection of ancient biblical manuscripts. Further, though they do not deal with Jesus or the early Christians directly, they are a tangible remnant of the era during which Jesus lived.

For other similar correlations between the biblical text and ancient sources, see Bible and Archaeology – Online Museum.