(Posted by Michael J. Caba)

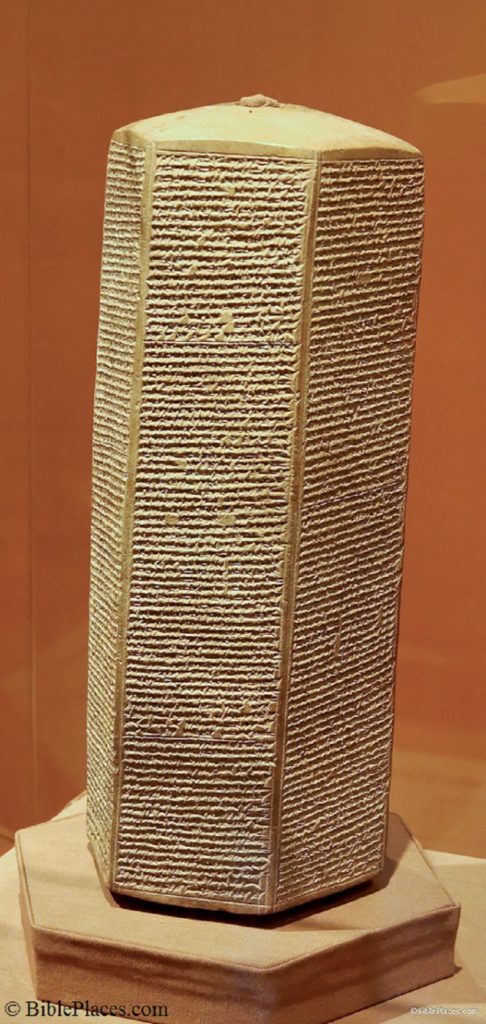

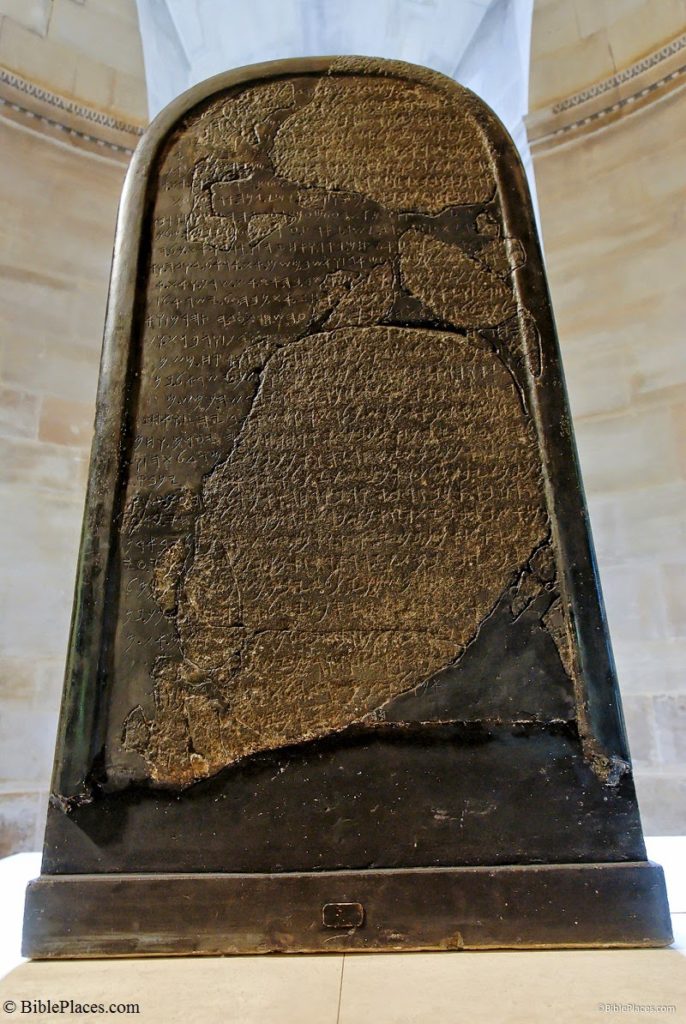

(Posted by Michael J. Caba)This inscribed basalt slab is known as the Stela of Zakkur. It refers to the Aramaic king Hazael who is also referred to in the Bible in such passages as 1 Kings 19:15. The item was discovered in 1903 at Tel Afis in Syria and dates to approximately 800 BC. The artifact is about 24 inches tall and the language is Aramaic. It is now located in the Louvre.

Of interest to historical studies is the interplay of the biblical text and this stela. To begin with, 1 Kings 19:15 says, “The Lord said to him [Elijah], ‘Go back the way you came and go to the Desert of Damascus. When you get there, anoint Hazael king over Aram . . .'” (NIV). In comparison to this, the text on the stela reads, “I am Kakkur, king of Hamath and Luash . . Bar-Hadad, son of Hazael, king of Aram, united against me seventeen kings . . .”

In effect, we have a web of connections linking Yahweh, Elijah, the Bible, Hazael, and this stela.

For information on similar artifacts related to the Bible, see Bible and Archaeology – Online Museum.

(Photo: BiblePlaces.com. Significant resource for further study: The Context of Scripture, volume 2, page 155.)