(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

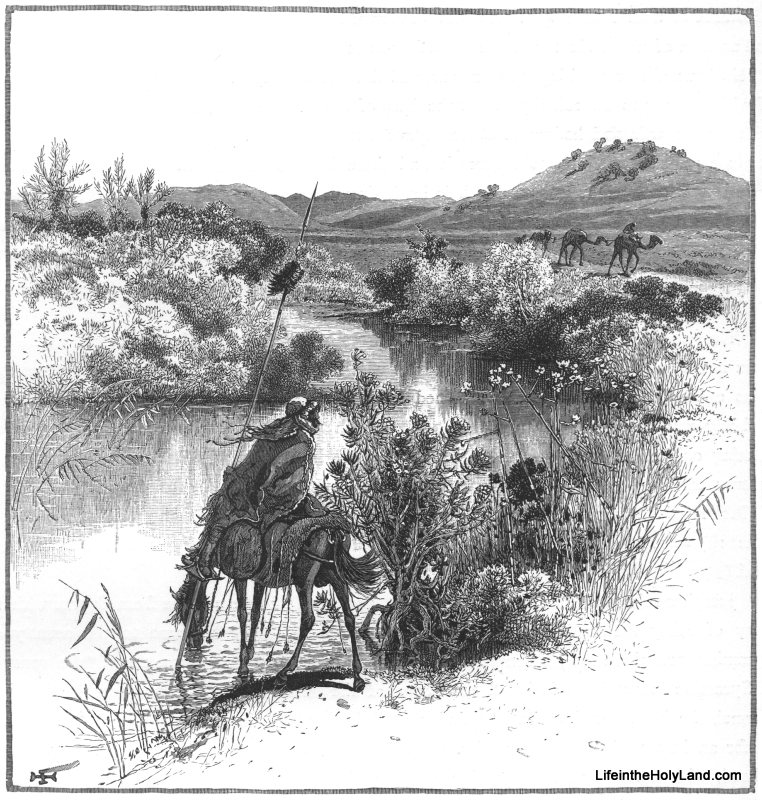

Our “Picture of the Week” focuses on the small, but significant, Kishon River. It is not a place that you would visit on a typical trip to Israel. In fact, I’ve been to Israel four times (two of which were extended stays) and I have never stopped there. Perhaps that is because the river does not look very impressive. Nevertheless, a couple of significant biblical events took place along this watercourse, and the geography surrounding and forming the river have played a crucial role throughout history.

The Kishon River drains much of the water from the Jezreel Valley and Lower Galilee. The Bible mentions this river by name a total of five times (Judg 4:7, 13; 5:21; 1 Kgs 18:40; Ps 83:9). It was here that Deborah and Barak defeated the 900 chariots of Sisera after gathering their forces at Mount Tabor, and it was here that Elijah had the prophets of Baal slain after the showdown on Mount Carmel.

In Judges 5:21, the Kishon is referred to as a “torrent,” but a visit to the site reveals that most of the time it is a rather timid river. In his book, The Geography of the Bible, Denis Baly describes the Kishon by saying:

Dry in its upper courses in summer, and only a trickle when it passes Harosheth [near its end], this famous stream is often a sad disappointment to visitors …

Yet on that fateful day in history, the river swelled with rainwater and swept away Sisera’s retreating army of chariots (Judg. 5:21).

The image above was a sketch of the river as it looked in the 1870s. At this location, the Kishon leaves the Jezreel Valley and enters the Plain of Asher through a narrow pass where the hills of Lower Galilee almost touch Mount Carmel. This choke-point is one of the reasons why the Jezreel Valley contains such rich soil. As the soil erodes into the valley from the surrounding hills, the river is not able to carry it out to sea. Instead, the river is blocked: first by a low ridge of volcanic rock that cuts across the valley in a northeast line starting near Megiddo, and then again by the foothills of Western Lower Galilee. Baly describes the outcome of these geographical features in this way:

The Kishon, small though it is, has to carry away the entire drainage from the surrounding hills, but it is twice hindered in this formidable task, once by the volcanic causeway and then again by the narrow defile through which it finds its way to the Bay of Acco. In consequence the two basins thus formed are only too easily flooded in winter, sometimes for prolonged periods, and W. M. Thomson, who knew the country well a century and a half ago, speaks of having “no little trouble with its bottomless mire and tangled grass.” In February, 1905, Gertrude Bell wrote even more feelingly of riding from Haifa to Jenin: “The road lay all across the Plain of Esdraelon … and the mud was incredible. We waded sometimes for an hour at a time knee deep in clinging mud, the mules fell down, the donkeys almost disappeared … and the horses grew wearier and wearier.” … Yet it was always “the rich valley,” for once dried out, the bottomless mud bears notable harvests.

So the Kishon River is not much to look at most of the time and until the rise of modern transportation it caused all sorts of difficulties for travelers during the rainy season when it flooded the valley. Yet for all this, it has played a key role in making the Jezreel Valley into a region of rich farmland. The fertile soil in this valley combined with the valley’s strategic location along the international trade route made the control of this area a coveted prize for many nations throughout history.

This image and 150 others (along with the entire text of Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt, Vol. 3) are available in Picturesque Palestine III: Phoenicia, Philistia, and the South. This digital volume can be purchased here for $20, or you can purchase all four volumes of the work for $55. Additional images of the Jezreel Valley can be seen here on the BiblePlaces website. Excerpts were taken from Denis Baly, The Geography of the Bible, new and revised ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), pp. 144, 146-147.