(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

This was a difficult week to come up with a photo to share. The problem wasn’t due to a lack of good material … the problem was that there were too many good photos available!

This week’s photo comes from Volume 2 of The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection, which focuses on Jerusalem. These are photographs of Jerusalem taken in the first half of the 20th century before many of the modern developments were built. So much has changed in the city since that time (both physically and politically) that this volume is a gold mine of material for Jerusalem studies.

Here is a list of some of the photos I could have chosen for this week’s post:

- The City of David when it was still being used for farmland.

- A German zeppelin hovering over the Old City.

- The interior of the Golden Gate on the Temple Mount.

- The interior of the Double Gate on the Temple Mount.

- The interior of Solomon’s Stables in the Temple Mount (but see here for a similar photo).

- The interior of the Hurvah Synagogue before it was destroyed in the War of Independence.

- The Pool of Hezekiah filled with water instead of trash (but see here for similar images).

- Sealed entrances to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

- The short-lived and aesthetically questionable clock tower built on top of Jaffa Gate (but see here for a previous post on that subject).

- Remains of a Crusader-period monastery in the Kidron Valley, a small portion of which was only briefly excavated in 1937 and then buried again.

- Crowfoot and Fitzgerald’s 1927-28 excavations in the City of David.

- A smog-free landscape looking east which includes the Hinnom Valley, Mt. Zion, the Judean Wilderness, the Dead Sea, and the mountains of Moab.

- The Jewish Quarter and the Western Wall as they looked before the War of Independence (but see here for a similar photo).

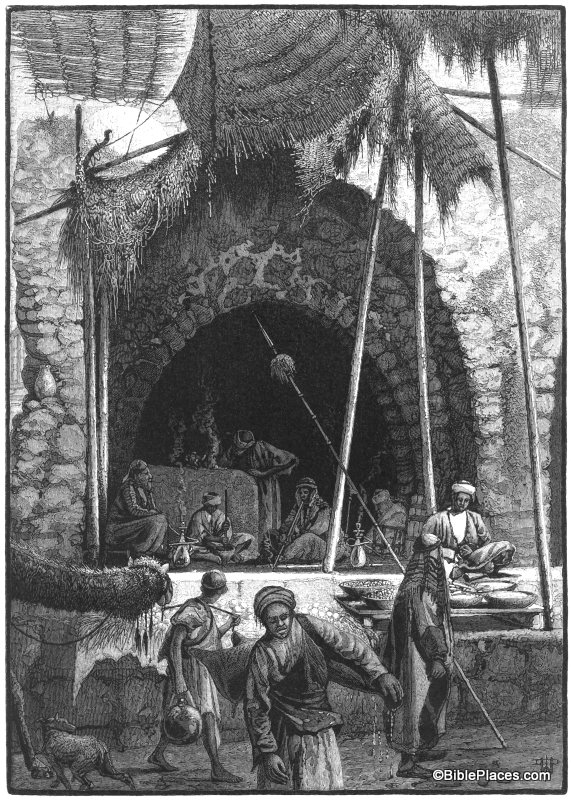

Instead, I will present the following rare photo of the interior of Barclay’s Gate (or at least the top section of the gate) on the western side of the Temple Mount, taken sometime between 1940 and 1946.

Barclay’s Gate was one of the entrances to the Temple Mount during the Second Temple Period (the time of Jesus and the apostles). A modern photo of the outside of Barclay’s Gate, in the women’s area of the Western Wall Plaza, can be seen here. Only the stone that formed the lintel is visible today from the outside. In the PowerPoint notes included in the collection, Tom Powers explains what we can see in the photograph above:

This fascinating photograph (looking northwest) shows a room lying beneath the surface of the Temple Mount (to Muslims, the Haram esh-Sharif, or “Noble Sanctuary”). This space was the subject of several descriptions and drawings by 19th century explorers but has rarely been seen by Westerners—or photographed. Much better known, actually, is the opposite side of the thick wall seen here at the end of the vaulted room: it is the massive lintel and blocked opening of an original western entrance of the Herodian Temple Mount, the so-called “Barclay’s Gate” partially visible in the very southern end of today’s Western Wall (women’s prayer area).

The ancient gate was identified in modern times by James T. Barclay, an American Protestant medical missionary and amateur explorer of Jerusalem’s ancient places. In the course of recounting his identification of the exterior gate elements, Barclay also described the space pictured here:

“During the period of my admission into the Haram enclosure I discovered in this immediate vicinity, on the interior, a portion of a closed gateway, about fourteen or fifteen feet wide; but whether it is connected with that on the exterior, I was not enabled to determine, for the guards became so much exasperated by my infidel desecration of the sacred room, el-Borak, where the great prophet tied his mule on that memorable night of the Hegira, that it was deemed the part of prudence to tarry there but a short time and never to visit it again . . . . Only the upper portion of the gateway can be seen—the lower part being excluded from view by a room, the roof or top of which is formed by the floor of this small apartment.”

— James Barclay, City of the Great King (1857), pp. 490-91

In the passage quoted above Barclay, alas, garbles some elements of the Muslim tradition (he calls the mythical beast a “mule” and confuses Mohammed’s Night Journey with the hegira, his flight from Mecca to Medina). Nonetheless, his notion that this “small apartment” might be connected to the gate he had identified from the outside was correct, as confirmed by other explorers only several years later. Barclay was also correct that the mosque occupied only the uppermost part of the gateway. But, whereas Barclay presumed the existence of a lower room, the mosque actually overlies a great volume of debris deposits (or fill) behind the blocked gate.

In this photo, the vaulting overhead is the top of the Herodian gate passage, and the dark line in the masonry of the far wall (beneath the shallow arch) corresponds to the bottom of the great lintel (apparently the lintel itself is not visible). Experts estimate the height of the Herodian gate opening, from sill to lintel, at 25 to 30 feet (7.8 to 9.3m), with the sill lying only a few yards (meters) above the Herodian street. Thus, in the original gate passage here, a broad stairway no doubt ascended (far beneath the floor shown here) toward the east and the surface of the Temple Mount. The original passage ran eastward from the western wall for at least 70 feet (22 m), but it was reconfigured and altered in many ways over the ages. For example, the distinctive arch of chamfered voussoirs (beveled and molded arch-stones) seen here, and others like it, point to a major redesign and rebuilding of the passage in Omayyad times (7th-8th centuries), when the gate was still open and in use. Since the Arab chronicler Al-Muqadassi in 985 still lists the gate (called by him, and all previous Arab sources, Bab Hitta) among the active entrances into the Haram, it must have gone out of use and was blocked sometime after that date. The eastern part of the passage was walled off at some point, plastered, and used as a cistern.

The “al-Buraq” Mosque pictured here, again, is built into the vaulted internal gate passage of Barclay’s Gate, along the western wall and inside the Haram (Temple Mount) enclosure. It is situated immediately next to the Mughrabi Gate, to the north, and below the level of the Haram platform, from which it is accessed by the two flights of stairs pictured here. The Matson-supplied date for this photo is 1940 to 1946, and the mosque apparently still exists today. …

This photograph and over 650 others are available in Volume 2 of The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection and can be purchased here for $25 (with free shipping). Other historic photos can be seen on various pages of LifeintheHolyLand.com. You can find the links the Jerusalem pages in the left column of the homepage.