Yesterday I gave the arguments for the view that includes Transjordan within the Promised Land.

This was the position of the other two faculty when I was teaching in Israel. I held to the opposing view, namely that the Jordan River is the eastern border of the “Promised Land.” Biblical evidence in support of this position includes the following:

1. The land promised to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob was “Canaan.” “The whole land of Canaan, where you are now an alien, I will give as an everlasting possession to you and your descendants after you” (Gen 17:8; cf. Exod 6:4; Lev 14:34). Countless passages make it clear that the land aspect of the promise included only Canaan. The biblical or extrabiblical descriptions of Canaan never include territory east of the Jordan River.

2. In preparation for the conquest, God said that the eastern border of the land they were to inherit would run from “the Sea of Kinnereth…down along the Jordan and end at the Salt Sea” (Num 34:11-12).

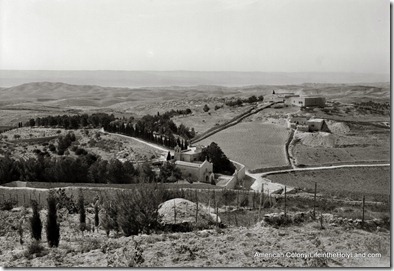

3. Moses was forbidden from entering the promised land; consequently he stood on Mount Nebo (which had already been given to the tribe of Reuben) to “view Canaan, the land I am giving the Israelites as their own possession” (Deut. 32:49).

4. If the land of the Amorites in Transjordan was part of what God had originally determined to give

the Israelites, Moses would not have bothered sending a request for safe passage through the territory of Sihon the Amorite. In any dealings with the “promised land,” Moses and Joshua simply destroyed the population without making any requests of them (e.g., Jericho, Ai, Hazor). It was only because Sihon refused to allow Israel to pass (perhaps thinking that the Israelites would leave him alone as they had done previously with the Edomites, Moabites and Ammonites) that the Israelites destroyed his army and their cities. As a result, the land was available for settlement and the two and a half tribes came to Moses with this special request.

5. After the Conquest, the two and a half Transjordanian tribes reported back to Joshua in order to receive permission to return to their land. Joshua said that this was “the land that Moses gave you on the other side of the Jordan,” explaining that it was legitimate for them to live there, but that it was not part of the original land of promise (Josh 22:4). Joshua also said that this land was “acquired in accordance with the command of the Lord” (Josh. 22:8), also indicating that such a notice was necessary because this was not part of Canaan granted to Abraham.

6. The construction of an altar by the two and a half tribes nearly resulted in a civil war. The Cisjordanian tribes accused their brethren of rebelling by building the altar near the Jordan River.

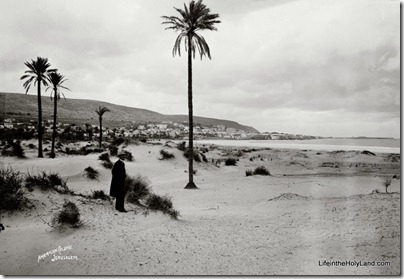

Note their statement: “If the land you possess is defiled, come over to the LORD’s land, where the LORD’s tabernacle stands, and share the land with us” (Josh 22:18). “The land” here clearly means “the land of promise.” The Transjordanian tribes respond that they built it only to prevent a future division between the tribes: “We did it for fear that some day your descendants might say to ours, ‘What do you have to do with the LORD, the God of Israel? The LORD has made the Jordan a boundary between us and you—you Reubenites and Gadites! You have no share in the LORD.’ So your descendants might cause ours to stop fearing the LORD” (Josh 22:24-25). God indeed had made the Jordan a boundary, not only a natural one, but one that defined the borders of the promised land and one that potentially threatened the nation’s unity.

7. In a period still future (best understood as applying to the earthly millennial kingdom), God will divide the land among the twelve tribes (Ezek 47:13-23). It will be divided equally among the tribes, with Joseph receiving two portions. “This land will become your inheritance.” The border is clearly demarcated on the eastern side of the Jordan River. “On the east side the boundary will run…along the Jordan between Gilead and the land of Israel, to the eastern sea” (Ezek 47:18).

Concluding Thought:

The issue is not whether or not it was legitimate for the two and a half tribes to settle in Transjordan.

Clearly this was granted by God. The question is whether or not this land was considered part of the everlasting “promise.” If the Transjordanian territory falls within the definition of “inherited” but not “promised” land, it may best be understood as the temporary but not eternal possession of the Israelites.