The Ancient World Online (AWOL) has several posts of map resources this week. The Digital Atlas of Roman and Medieval Civilizations is a work-in-progress by students and faculty at Harvard. The Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem has now made available online the Eran Laor Cartographic Collection. For more historic maps, start with the Links page at this site.

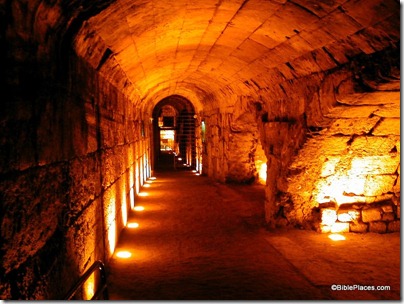

Tom Powers reports that you can now walk underground (on the street and through the drainage channel) from the Pool of Siloam to the Givati Parking Lot opposite the entrance to the City of David. He also has photos of the new exit for the passage just below Robinson’s Arch. (The unsightly railing smack in the middle of the first-century street will cause distress for those who haven’t already taken photographs of this historic site.)

The Jerusalem municipality is promoting a “Take two days in Jerusalem” campaign this summer, and the list of cultural events is extensive:

The International Festival of Light, Knights Festival, International Film Festival, Puppets Theater Festival, Opera Festival, Balabasta Festival in Mahane Yehuda Market, Jerusalem Beer Festival, Arts & Crafts Festival, End of Summer Celebration Festival, Wine Tasting Festival, Shalem Dance Festival, Ziggy Marley, Infected Mushrooms, Matisyahu, Eyal Golan, Renee Fleming and more!

Arutz-7 is reporting illegal construction activity at Gibeah of Saul.

Recent events in the Middle East may have a downside: “The ‘Arab Spring’ may have facilitated trade of a treasure trove of stolen assets in the world’s art and antiquities markets.”

The Ashmolean Museum at Oxford will be opening new wings for ancient Egypt and Nubia in November.

Amihai Mazar will be giving a public lecture in Sydney, Australia in September.

HT: Joseph Lauer, Jack Sasson, BibleX