2008 was a good year for archaeology. You can read about the top ten archaeological discoveries in the world this year, but my goal here is simply to suggest what I perceive to be the most significant discoveries for understanding the Bible and its world. Both the selection and the ranking is purely subjective; there were no polls, editorial committees, or coin tosses. For another opinion, take a look at the list of Dr. Claude Mariottini.

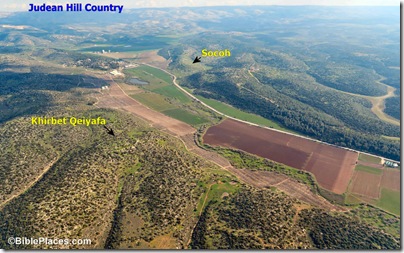

1. Khirbet Qeiyafa (and inscription). The new excavations of this fortified site in the Shephelah ranks as #1 for the following reasons:

1) The site was occupied for only a limited time during the reign of King David.

2) The site is located near the battle location of David and Goliath.

3) A strongly fortified site is indicative of a strong central government, at a time when scholars

question the existence of such.

4) A early Hebrew inscription discovered this summer points to the site’s owners (Judeans) and the state of literacy in this period.

5) These discoveries will certainly shed light on what is currently the most debated issue in biblical archaeology: the nature of Israel/Judah during the 10th century.

2. Gath excavations. It’s not a single discovery that puts the excavations of this Philistine city in the number two spot, but rather the cumulative results of a very profitable season. This includes possible early Iron IIA material (see above debate), a 10th century seal impression, two Assyrian destruction layers, methodological advances, as well as other significant remains from the Early, Middle, and Late Bronze Ages.

3. New discoveries at Herod the Great’s tomb. The tomb was discovered and identified in 2007, but on-going excavation in 2008 revealed additional coffins, including one that may belong to one of Herod’s wives and another to one of his sons. They also found a theater that sat 750 people and included a VIP room with beautiful wall paintings. All of this further confirms the previous identification that Herod’s tomb was located on the slope of the Herodium.

4. The “First Wall” of Jerusalem. A well-preserved portion of the Hasmonean wall (2nd century B.C.) was uncovered on the south side of Jerusalem. While parts of this wall have been excavated previously, there are two advantages to the current excavation:

1) It is being carried out with the latest in archaeological knowledge.

2) The remains will be preserved and visible to visitors.

5. Alphabetic Inscription from Zincirli. The Kuttamuwa Stele is a large well-preserved funerary inscription from the 8th century B.C. city of Sam’al (modern Zincirli) that sheds light on the beliefs of the afterlife of one of Israel’s northern neighbors. For more on the content of the inscription, see this. This is the only discovery on this list which is also on Archaeology Magazine’s Top 10 Discoveries of 2008.

6. Iron Age Seals from Jerusalem. Many inscriptions were found in Jerusalem at different times this year, including the Seal of Shlomit (aka Temah), the Seal of Gedaliah, the Seal of Netanyahu, and the Seal of Rephaihu. The first two were discovered in Eilat Mazar’s excavation of the potential area of “David’s palace,” and the other two were found relatively close by (Western Wall and Gihon Spring). Gedaliah is mentioned by name in Jeremiah 38:1, and Shlomit may be mentioned in 1 Chronicles 3:19. Some might rank these discoveries higher in the list, but I have not because so many have already been found, including many in this area and many that mention other biblical figures.

7. Pre-8th century B.C. neighborhood in the City of David. This report received little notice, as far as I could tell, but could be quite significant in our understanding of the growth of Jerusalem in the earliest centuries of Judean rule. While these discoveries were made in 2007, they were only publicized in 2008 (thus qualifying them for this list). In short, the archaeologists found five Iron Age strata which included a group of houses that dated “earlier than the 8th century.” Excavators rarely uncover houses in Jerusalem, and these would be the earliest I know of from the Iron Age.

8. Philistine temple near Gerar. I heard very little of this discovery, but it makes the list because Philistine temples are both rare and of biblical interest (see Judges 16:23-30 and 1 Samuel 5:2-5).

Other Philistine temples have been excavated at Tel Qasile and Ekron (and Aren Maier has teased that he may have another at Gath).

Other discoveries that did not make the top 8 include the sarcophagus fragment of the son of the High Priest in Jerusalem, the “Christ Inscription” in Egypt, and a Jerusalem quarry found in Sanhedria.

The on-going Temple Mount sifting project deserves mention (and support).

Other finds that did not make the list are the perfume bottle that Mary Magdalene used to anoint

Jesus’ feet and the water tunnel that David used to conquer Jerusalem. Perhaps more information or discoveries will convince me that these are more than attempts to gain publicity.