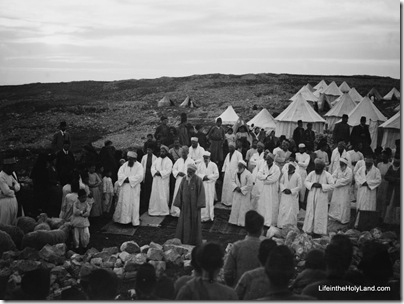

Snow flurries drifted to the ground on Mount Gerizim overlooking Nablus on Thursday, as mourners gathered to bury the spiritual leader of the Samaritans, who passed away the previous day.

High Priest Elazar ben Tsedaka ben Yitzhaq was born during a snowstorm 83 years ago, one mourner said. On Thursday, as he was being laid to rest at the holiest site in the Samaritan religion, the snow began to fall again.

According to Samaritan tradition he was the 131st holder of the post since Aaron. This is not be accepted by all historians, but the office may well go back to the Hellenistic period, which would still make it the oldest office in the world. One account in Josephus suggest that it is an offshoot of the Zadokite high priests in Jerusalem from around the time of Alexander the Great.

Mourners took shelter from the storm inside the community center in the hilltop neighborhood of Kiryat Luza, where much of the ethnoreligious group of 730 lives. Nearly all the rest live in Holon’s Neveh Pinchas neighborhood.

Inside, well over 100 men gathered in a somber, eerily quiet ceremony around the casket holding Elazar, who will be replaced as head priest by his cousin Aharon Ben-Av Hisda Cohen.

The Samaritans are a tiny, largely misunderstood sect that practices a religion that is a close parallel to Judaism. Samaritans believe theirs is the true religion of the Israelites and follow their own Samarian Torah, written in an ancient form of Hebrew largely alien to modern Israeli eyes. Today’s Samarians trace their lineage to Israelites who have lived in northern Samaria before the Babylonian exile, and they still view Mount Gerizim, not Jerusalem, as the center of their religion.

The new High priest is a prominent scholar in the community, a poet, and an expert in the calculation of the Samaritan yearly calendar. He was born in Nablus/Samaria in 1927. He had been a high school teacher of mathematics for many years in Nablus and after his retirement devoted himself to matters of the priesthood, literature and research. High Priest Elazar participated in research delegations on Samaritan manuscripts in St. Petersburg in 1991 and in political issues to Washington D.C. in 1995.