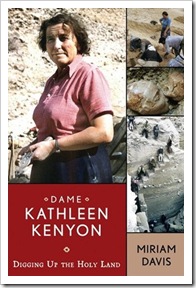

Kathleen Kenyon was recently the subject of a biography written by Miriam C. Davis. Dame Kathleen Kenyon: Digging up the Holy Land was reviewed in Haaretz by Magen Broshi, an archaeologist and the former curator of the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. His review begins:

She never married, and her friends described her as a person whose world consisted of three loves: archaeology, dogs and gin. Kathleen Kenyon was also the head of a women’s college at Oxford. She bombarded the press with anti-Zionist and anti-Israel articles and letters − she thought that the Muslims had preferential rights to the Land of Israel because they had been living there for 1,400 years, whereas the Jews had ruled the land only during the First Temple period (about 400 years) and for another 100 years, during the Hasmonean dynasty. She was, however, one of the most important archaeolo gists ever to dig in the Land of Israel.

gists ever to dig in the Land of Israel.

That is not a negligible achievement, because more archaeological work has been done in the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, in other words in the State of Israel and the territories, than anywhere else in the world. There is no other country that has been so thoroughly researched, and the number of digs and surveys carried out here is incomparably greater than what has been done in far larger countries. Kenyon is not only one of the most important archaeologists to have worked here (and they number over 1,000), she is also the leading female archaeologist to have worked anywhere (along with the prehistorian Dorothy Garrod).

Broshi looks primarily at the three sites in the Holy Land that she excavated, Samaria, Jericho, and Jerusalem. Concerning the last:

The final site excavated by Kenyon was Jerusalem, and here she was not so lucky. In effect, the digs there, as they are described in the book, were post-climactic. Despite the huge investment – seven digging seasons between 1961 and 1967 – with up to six sites operating simultaneously, employing hundreds of workers, the results were small in number and also unimportant. One reason for this is that while Jordan was still in charge of the old city, Kenyon was not permitted to work in the areas where other archaeologists – like Benjamin Mazar, who excavated south and southeast of the Temple Mount, and Nahman Avigad, who worked in the Jewish Quarter – later discovered many important finds. (Kenyon’s work was restricted because the Waqf Muslim religious trust was opposed to excavations in the Jewish Quarter, since there were Palestinian refugees living there).

The second reason is related to the limitations of her modus operandi, the Wheeler-Kenyon method, which relied on examinations in a limited zone and refrained from exposing a horizontal area. Careful examinations in pits, as meticulous as they may be, are likely to lead to a result similar to that of the Indian fable about the three blind men who fell on an elephant but were unable to identify it correctly: The person who fell on the tail shouted “ropes,” the one who encountered the legs declared “planks,” and the third, who climbed on the tusks, yelled “swords.” Only a dig that exposes a horizontal area is likely to take in the whole “elephant.”

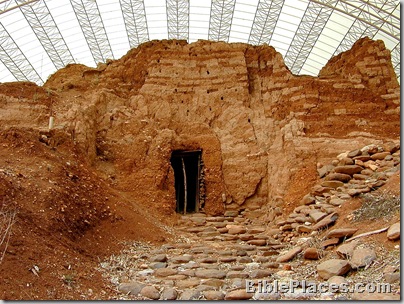

Wadi Murabaat = Nahal Darga, Cave where Bar Kochba scrolls found

Wadi Murabaat = Nahal Darga, Cave where Bar Kochba scrolls found