(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

Our picture of the week focuses on the obscure site of Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula. This is not a place that you will visit on your typical tour of Egypt. In fact, it was not a place that even many ancient Egyptians would have visited!

Located about 17 miles (27 km.) from the Gulf of Suez, Serabit el-Khadim was a mining site. Teams of miners would be sent to this region by the Pharaoh to dig up turquoise and copper. However, this was only carried out during times when there was a strong central government in Egypt. The site was occupied on and off from the time of the 4th Dynasty (c. 2600 B.C.) to the time of the 20th Dynasty (c. 1100 B.C.) The following map, which is included in Volume 7 of the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands, shows its position near the Gulf of Suez. (A special thanks is due to A.D. Riddle who created the original maps in the PLBL and has volunteered to customize those maps for this series of blog posts.)

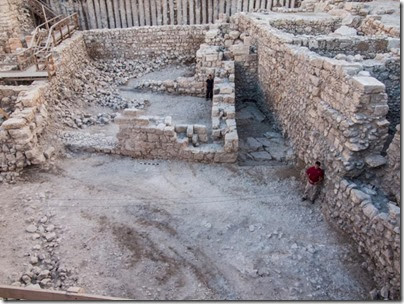

Pictured below are the ruins of the Temple of Hathor that stood at this site and the scorching desert of the Sinai spreading out below it. Starting with a small shrine within a cave, this temple complex grew larger and larger over the course of several hundred years as successive Pharaohs each added their own special touch.

In The Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land, the temple and its development is described in the following way:

During the excavations an early high place, and a series of temples that replaced it, were revealed within a temenos (enclosure), 200 feet by 140 feet in area. The original Egyptian shrine consisted of a cave sacred to Hathor, goddess of the land and of minerals. In front of the cave a portico was constructed, and then a large court; and further shrines were added during the long Egyptian occupation of the site. Within the temenos were caves dedicated to other deities, such as the moon-god Thoth.

Mining of turquoise did not begin at Serabit el-Khadem until the time of the 12th Dynasty …. Turquoise was essential to the Egyptian jewelry industry, while copper was important for the production of tools and weapons …. The earliest Egyptian monarch to send an expedition to Sinai was Sneferu, the first king of the 4th Dynasty. Mining continued with some interruption down to the end of the 6th Dynasty, when both mines were again worked under Ammenemes III of the 12th Dynasty. Stalae set up in the temple record the various mining expeditions, of which no less than seven took place during Ammenemes III’s reign. …

The temple of Serabit el-Khadem had been enlarged repeatedly. Continuing the process, Sethos I, founder of the 19th Dynasty, extended it. Rameses II and Merneptah are also recorded in the temple, as is Rameses III of the 20th Dynasty. At the beginning of the 21st Dynasty the mines of Sinai went out of use once more.

This map and photograph, along with over 1,000 other images, are available in Volume 7 of the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands, available here for $34 (with free shipping).

Excerpt is taken from “Serabit el-Khadem,” in The Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land, Logos Edition, ed. Avraham Negev (New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1990).