(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

After a holiday break, we are back with the next installment of our series on “obscure sites in the PLBL.” Today we will be focusing on the Neolithic site of Catalhoyuk in central Turkey. Like many archaeological sites, at first glance this location looks like a normal hill. But there is much more than meets the eye…

The PLBL provides the following general information about the site in the PowerPoint annotations:

Çatalhöyük (Catal Hoyuk, Catal Huyuk) is located in the Konya Plain, about 21 miles (37 km) southeast of Konya

(ancient Iconium). It is the largest Neolithic site that has been discovered and is very

well-preserved. The site consists of two flat mounds, a large mound to the east

and a smaller mound to the west. The mounds are said to resemble the shape of a

fork, hence the name of the site (çatal is Turkish for fork). The eastern

mound of Catalhoyuk rises 65 feet (21 m) above the surrounding plain and covers an area of 32

acres (13 ha). Thirteen occupational strata have been excavated dating to the Neolithic

period, the earliest of which dated to ca. 7200 BC and the latest to ca. 5500

BC. The town had a population of up to 8,000 people.

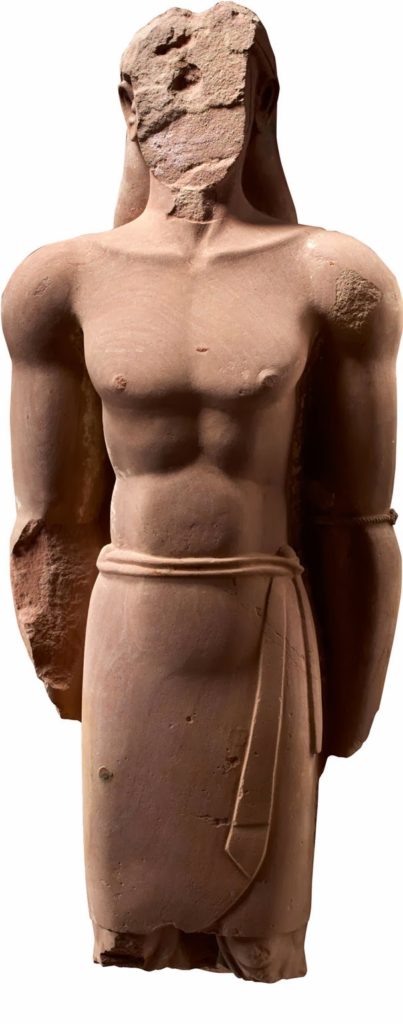

And the surface of the tell is nothing to write home about, as you can see in the photograph below.

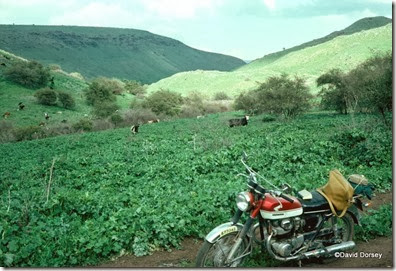

However, there are some striking features about this site. As the archaeologists dug into the tell, they discovered a city that was comprised of houses connected to houses with no streets. It appears that the inhabitants of the city walked over the flat roofs of the houses to get from one end of town to the other! Below is a photograph of some of the excavations being conducted at the site. (You get two-for-one this week.)

Again we turn to the annotations in the PLBL for more information:

Catalhoyuk is made up of domestic dwellings

packed together without any streets. The people moved about on the roofs of the

houses and entered the houses through holes using ladders. The houses were made

of mudbrick and the interiors were plastered and decorated with murals. Houses

typically consisted of two rooms with raised platforms along the walls…. An oven was often

located near the ladder, beneath the hole in the roof. Throughout the town,

there are a number of large courts.

So the next time you are tempted to complain about your neighbor’s kids playing too loud in the backyard or the high volume of traffic that passes in front of your house, just be grateful that you don’t live in the ancient city of Catalhoyuk where your neighbors would have walked on your roof on their way to work.

These photographs and annotations are available in Volume 9 of the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands and is available here for $34 (with free shipping). Other photographs from this volume can be seen here, here, and here.

A helpful video that shows a reconstructed time lapse of how the city was built and the ruins were formed can be found here.