Using satellite images, a researcher has identified potentially 9,000 new sites in northeastern Syria.

“With these computer science techniques, however, we can immediately come up with an enormous map which is methodologically very interesting, but which also shows the staggering amount of human occupation over the last 7,000 or 8,000 years.”

The Jezreel Expedition “just released three-dimensional LiDAR models detailing the site’s architecture and ancient landscape taken from recently collected LiDAR data.”

The spring season at Tel Burna has ended.

A writer for the Detroit Free Press describes one day on a dig at Khirbet Qeiyafa.

A New York Times article describes problems facing archaeologists returning to Iraqi sites.

Travelujah tells the “beautiful and tragic” story of Naharayim and Peace Island.

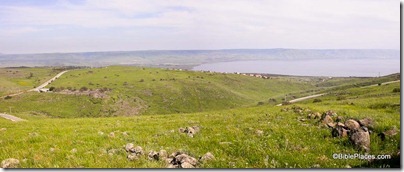

Joe Yudin visits Chorazin this week.

The Winter 2012 issue of DigSight is now online (pdf). Topics include: The “Jesus Family Tomb”

Revisited, The Oldest Egyptian Reference to Israel?, Recent Sightings, and Upcoming Events.

James Tabor: “Discovery TV has confirmed that the one hour special titled ‘The Resurrection Tomb’

will air on Thursday, April 5th, at 10pm EST.”

Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, the previous work by Lois Tverberg and co-author Ann Spangler, is

available for $3.99 for Kindle for a few more days.

HT: ANE-2, Joseph Lauer, Jack Sasson

Chorazin from the west