Over the next week or so I will be discussing a topic of considerable interest to this author – the identification of Beth Haccherem. My conclusions are not revolutionary (or new), however, the methodology with which I reached my conclusion has not been used elsewhere (at least according to my knowledge.) With that being said allow the following information to inform and introduce you to the ancient site of Beth Haccherem.

Site Name

Beth Haccherem literally means “the house of the vineyard.” The name testifies to the city’s location and function. The Judean hill country’s vine-producing capabilities are some of the best in the Levant. Beth-Haccherem is within a larger group of sites with names derived from agricultural man-made devices.

p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

Textual Concordance (source document, available on request)

@font-face {

font-family: “Courier New”;

}@font-face {

font-family: “Wingdings”;

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraph, li.MsoListParagraph, div.MsoListParagraph { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }ol { margin-bottom: 0in; }ul { margin-bottom: 0in; }

1. Joshua 15:59a (LXX) (you can download a free translation of the LXX here)

2. Jeremiah 6:1 (key verse)

3. Nehemiah 3:14 (updated – not 3:1)

4. Genesis Apocryphon 22:13-14 (Dead Sea Scrolls)

5. The Copper Scroll X:47-51 (Dead Sea Scrolls)

6. Midoth 3:4 (Mishna)

7. Niddah 2:7 (Mishna)

8. Jerome – Jeremiah Commentary (v. 6:1)

Proposed Identifications

@font-face {

font-family: “Courier New”;

}@font-face {

font-family: “Wingdings”;

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraph, li.MsoListParagraph, div.MsoListParagraph { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }ol { margin-bottom: 0in; }ul { margin-bottom: 0in; }

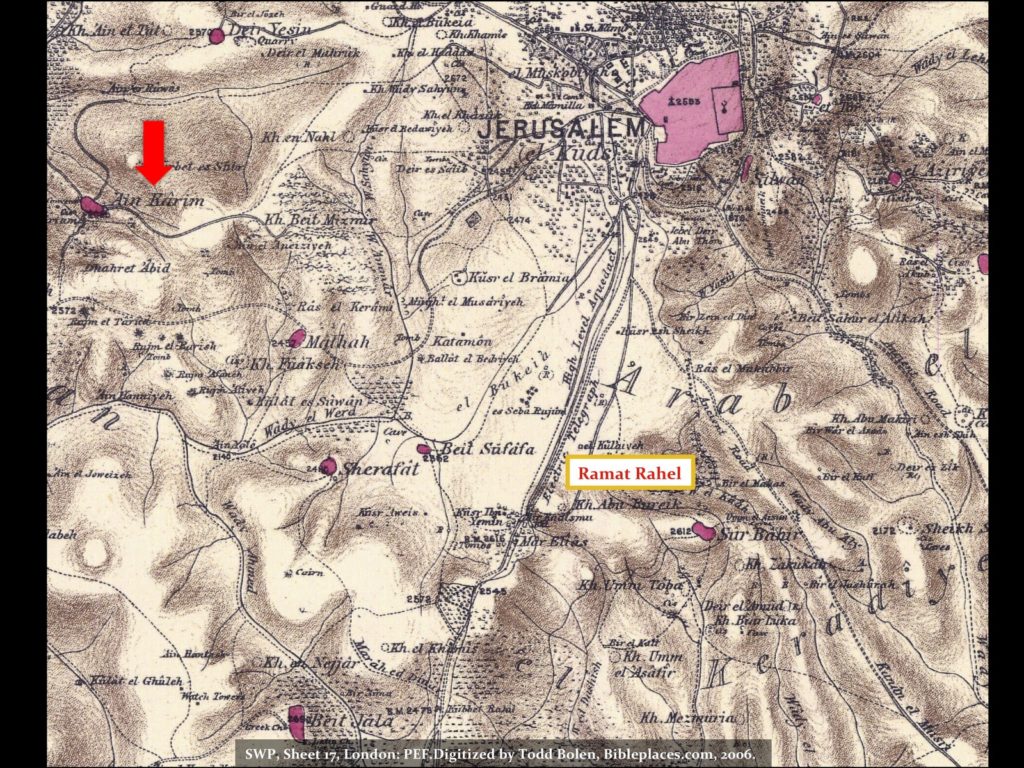

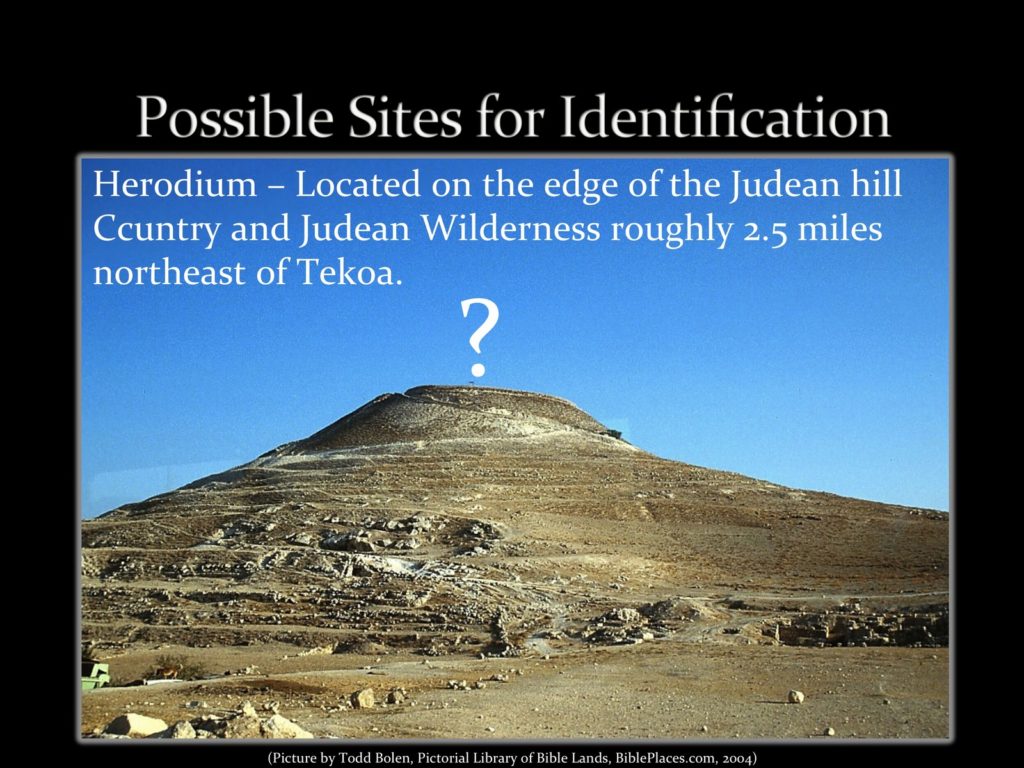

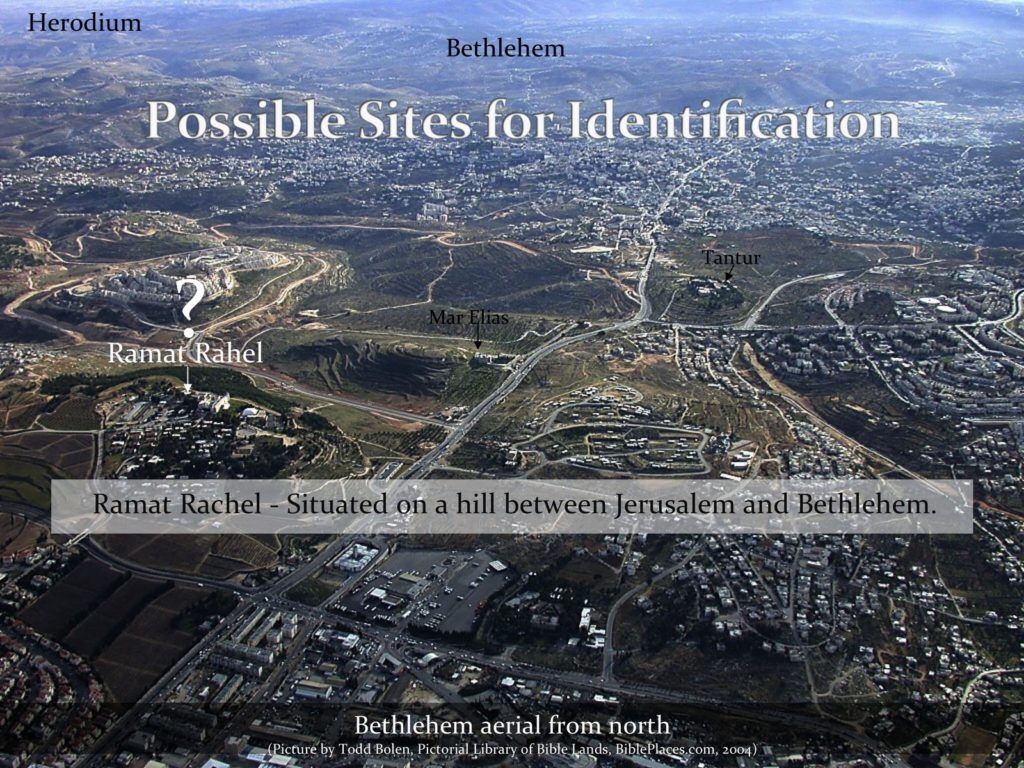

- Herodium (Edward Robinson 1838)

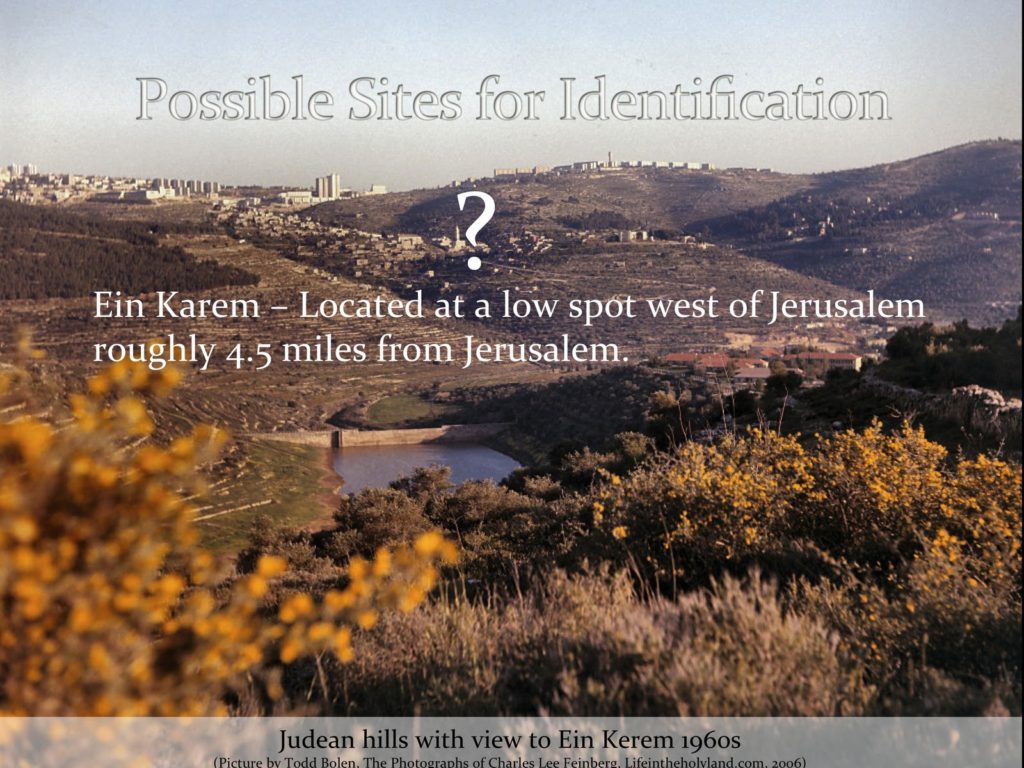

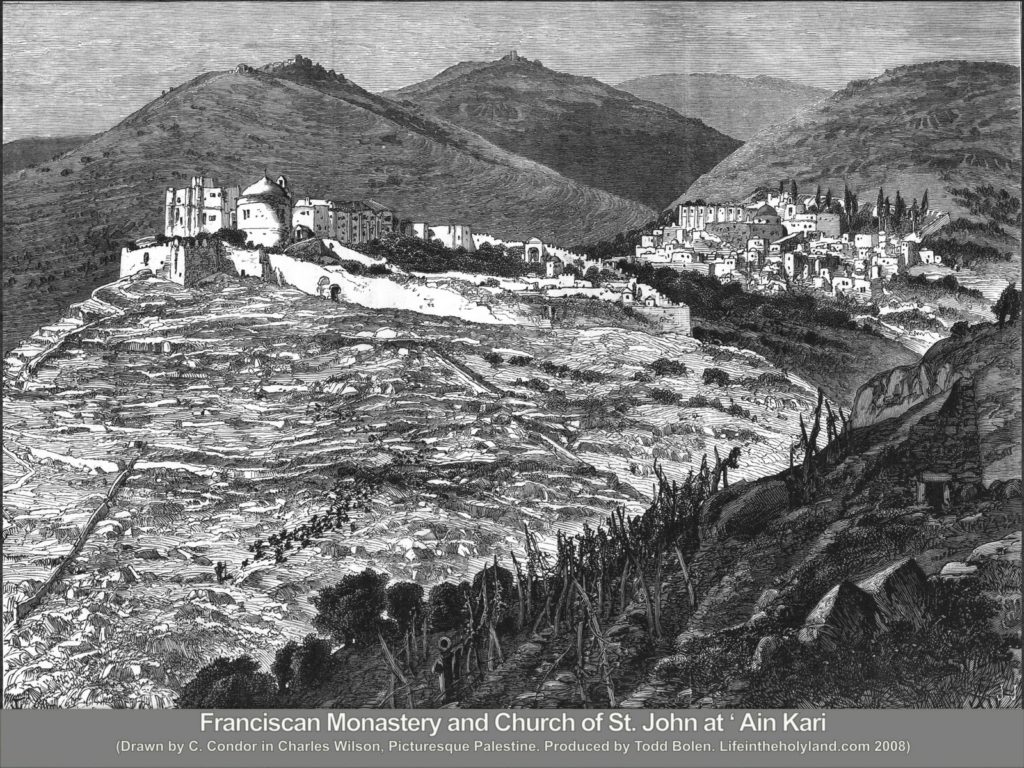

- Ein Karem (Edward Robinson 1856 – traditional identification)

- Ramat Rachel (Yochanan Aharoni 1950s)

|

| Map of proposed sites (click on images to zoom) |

Possible Toponymic Connections

@font-face {

font-family: “Courier New”;

}@font-face {

font-family: “Wingdings”;

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraph, li.MsoListParagraph, div.MsoListParagraph { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt 0.5in; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }ol { margin-bottom: 0in; }ul { margin-bottom: 0in; }

- Jebel Fureidis (modern – Herodium) – Arabic meaning “mountain of Herod.”

- Ain Karem (modern – Ein Karem) – Arabic meaning “spring of the vineyard.”

- Khirbet Salih (modern – Ramat Rahel) – Arabic meaning “ruin of Salih” unlike many place names it is not a variant of some ancient place name.

More to come…

Akhenaten Statue before looting (www.drhawass.com).

Akhenaten Statue before looting (www.drhawass.com).