From Arutz-7:

A recent report by engineers says that the condition of the Mugrabi Gate is continuously deteriorating and that a few incidents of rocks collapsing from it were recently reported.

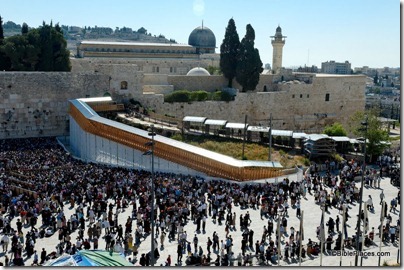

The Mugrabi Gate is the only entry point for Jews and other non-Muslims to the Temple Mount.

Jerusalem District Archaeologist Yochanan Zeligman recently addressed a letter to Israel Antiquities Authority Director-General Shuka Dorfman, in which he warned that “a danger exists to the crowd in the women’s section of the Western Wall Plaza, as well to those who walk on the temporary bridge, should stones fall from above.”

The temporary bridge to which Zeligman referred is a wooden pedestrian pathway to the Temple Mount which was constructed in 2007 after a landslide two years earlier made the earthen ramp leading to the Mugrabi Gate unsafe and in danger of collapse. Zeligman’s letter was based on a report he submitted which determined that since the construction in the Mugrabi Gate has not yet been completed, there are sections which are unsupported and could endanger visitors to the site.

Archaeologist Dr. Gabi Barkai, Jerusalem Prize Winner, member of the Committee for the Prevention of the Destruction of Antiquities on the Temple Mount, and lecturer at Bar Ilan University, spoke with Arutz7 on Thursday and expressed his sorrow that the Mugrabi Bridge is not being maintained for illogical political reasons.

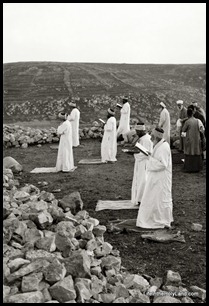

The story continues with Barkai giving the background to the ramp. The Temple Mount was closed to non-Muslims until 2003, not 2008 as stated in the article.