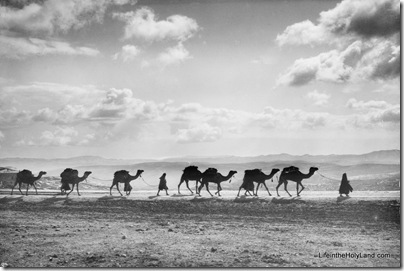

“The camels of loaded caravans are usually fastened one behind another in single file, and thus make one deep track or footpath; but in the Haj and in a small party like ours, they are left to choose their own way, and seldom follow each other in line; so that many parallel tracks are thus formed” –Edward Robinson and Eli Smith, Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petrea (1841): 1:60.

“The first time I came up this road from Jaffa, many years ago, midway between Upper Beth-horon and el Jîb, in the narrowest and most difficult part of the pass I encountered a long and straggling drove of camels—more than five hundred—which Ibrahim Pasha had bought from the Arabs east of the Jordan, in order to transport provisions and war material for his army. Though I have since seen many thousand camels in one caravan of the Wuld ‘Aly—some said fifty thousand—that sight did not affect my imagination to an equal degree. Those five hundred loose camels, with their Bedawin drivers shouting to them at the top of their voices, came lunging and plunging down the rocky path in wild confusion; and my terrified horse becoming quite unmanageable, rushed away amongst the rocks, to the no slight danger of breaking his own neck and that of his rider” –William M. Thomson, The Land and the Book (1882): 2:73.

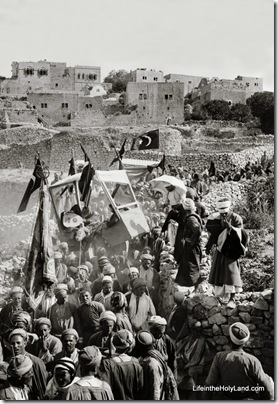

The photo and quotations are taken from the Traditional Life and Customs volume of The American

Colony and Eric Matson Collection (Library of Congress, LC-matpc-04570).