Looking back over the year is a profitable exercise for me personally because I forget so much and so quickly. Perhaps it is the volume of information coming from all corners of the globe that trains the mind to retain very little. A review of the posts here over the past year reminds us of recent history

but it also allows us to judge what was more important and what was less.

I have compiled several lists of “top stories.” Today we will review major discoveries, top technology-related stories, and losses. Tomorrow we will survey significant stories, noteworthy posts, and favorite resources of the year.

I do not deny that what is judged “top” in these reviews may tell the reader more about us than it does about the world of biblical archaeology. These lists are entirely subjective, and since they are based on what we decided to post (and not to ignore), they are doubly subjective. The primary criteria for selection was that the story was posted on this blog and then it caught my eye when I reviewed the year’s stories. The lists follow a roughly chronological order.

Top Discoveries of 2011:

Jerusalem Water Channel (and here and here and here and here)

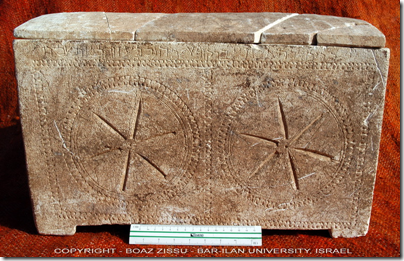

Ossuary of Caiaphas’ Granddaughter Recovered

Lion Statue Found at Tell Tayinat, Turkey

Philistine Two-Horned Altar from Tell es-Safi (and here)

Golden Bell Discovered in Jerusalem and Recording Released

Ancient Sabbath Boundary Inscription in Galilee (and here)

Hercules Statue Discovered in Jezreel Valley

Roman Sword and Menorah Depiction Found in Jerusalem

Largest Mosaic Discovered in Antioch

Mikveh Discovered near Biblical Zorah

Western Wall Discovery: IAA Desperate for Headlines (and here)

Mysterious Marks in the City of David (and here)

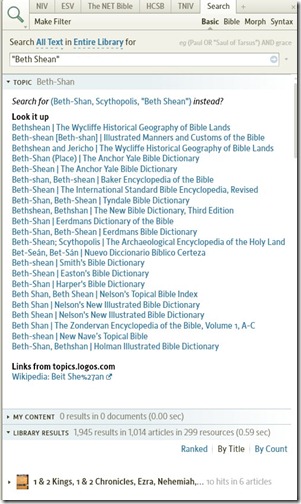

Top Technology-Related Stories of 2011:

Archaeology in Saudi Arabia with Google Earth

X-ray Vision for Archaeologists: The “Multi-PAM” Tool

Kinect Game System To Be Used in Jordan Excavation

Five Dead Sea Scrolls Online in High Resolution

InscriptiFact: A Better Way To Read Inscriptions (and here)

Losses:

Anson F. Rainey (and here)

Photo by Boaz Zissu, Bar-Ilan University