If you think that archaeology is boring, you should take thirty minutes this weekend and read Asaf Shtull-Trauring’s article in the Haaretz magazine. This lengthy piece interviews the major players in the chief dispute in Israeli archaeology today. Those familiar with the minimalist-maximalist debate over the United Kingdom of Israel will find a good bit that is new. Those looking for an introduction to the conflict can hardly do better than start here.

If I had the time, I could interact extensively with this article. Instead, I am going to choose a few items that caught my attention and provide my own (brief) commentary.

Yosef Garfinkel on Khirbet Qeiyafa:

According to him, this site, which he has been excavating for the past four years, constitutes the definitive proof for the existence of a city that was part of the Kingdom of David in the 10th century BCE. “It is the first and last evidence,” he says. “Until now nothing similar has been found anywhere in the country.”

Beware of bold claims like this one. Four years is hardly enough time to convince your skeptics, and even your friends should be suspicious. It is no wonder that Garfinkel has won no one over to his side.

Eilat Mazar on Khirbet Qeiyafa:

“The site definitely reflects a capable government, which necessarily rested on a periphery,” says Dr. Eilat Mazar from the Hebrew University, one of the salient members of the school that theorizes the existence of a large developed kingdom. “In light of these ruins, is it possible to assume that no broad periphery exists? That is unthinkable,” she insists.

This is a very important point that is not addressed by the minimalist camp in this article.

Garfinkel on his agenda:

“I did not come here to look for David. I had no opinion in those debates; I was tabula rasa,” he says – a clean slate. After many of the previous generation of biblical archaeologists had retired, he says, his department looked for researchers to conduct excavations relating to the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Since Garfinkel claimed in his first year at the site that he had found the grand site of Azekah, I am very reluctant to believe that his first priority was something other than making a name for himself.

(He quickly abandoned that silly idea when he found something else he could talk to newspaper reporters about.)

Garfinkel on identifying Qeiyafa as Shaaraim:

“You won’t find another city in Israel or Judah with two gates,” he notes, and adds, “In the Bible, Sha’arayim is mentioned only in the Davidic period, in the region of Elah Valley: when David kills Goliath, the Philistines escape via Sha’arayim.”

Actually Shaaraim is mentioned in Joshua 15:36, hundreds of years before David’s time. The context there argues against Garfinkel’s identification (but that’s another matter for another day). But notice too, if the interviewer quoted Garfinkel correctly, that the archaeologist admits evidence that dooms his identification. If the Philistines escape via Shaaraim (as they do; see 1 Sam 17:52), then Qeiyafa cannot be Shaaraim, unless you want to argue that the Philistines climbed up the hill to the city (Qeiyafa) as they were fleeing west to Gath. Actually, nothing about the Shaaraim identification works. As for whether Garfinkel found two gates, keep reading…

On the maximalist revival:

Thus, the proponents of the biblical approach now feel they can hold their heads high after years of fighting a rearguard battle against Finkelstein and his colleagues.

First, Finkelstein has only been making this case for 16 years. That’s but a brief season in the scope of scholarship. Second, this period of time of “advance” by the minimalists has been entirely under the shadow of the discovery of the Tel Dan Inscription with its undisputed reference to the “house of David.” If there is an area in which the maximalists may have felt left behind, it is in matching the sales of Finkelstein’s popular books attacking the Bible. If you want to hear something new, buy a Finkelstein book. Those maximalist guys keep saying the same things we’ve heard for decades.

Eilat Mazar on her discoveries:

“No one agrees with what I say,” Mazar admits, though her confidence appears unshaken.

Conservatives who find in Mazar statements that agree with their conclusions would do well to remember this. Like Garfinkel, Mazar has a penchant for discovering the most impressive items the very first season, and these finds always support their own viewpoints. Conservatives would do well to view their claims with a critical eye, especially if they accord with their own inclinations.

On excavations of copper mines:

The American anthropologist Prof. Thomas Levy, from the University of California, San Diego, is currently excavating at Khirbat en-Nahas in southern Jordan, which was a large copper mining center in the Iron Age and is located in a region thought to have been under the control of the Edomites. Three years ago, Levy, using carbon-14 dating, dated the site to the end of the 10th century BCE, the Solomonic period.

These are potentially very important. How they fit into the overall picture is yet to be determined. Finkelstein’s criticisms on this matter must be taken seriously.

Garfinkel on the significance of his four years of excavation of Qeiyafa:

“Our dating destroyed the low chronology,” he says with satisfaction.

Oh, boy. This may get invitations to speak at non-academic conferences, but it convinces no one in the field. It’s hard for me to believe that an archaeologist would dare make such a statement about his own work. Maybe after thirty years of work at multiple sites, one could be so confident.

On Yigael Yadin and Benjamin Mazar:

They aimed to provide roots for the nation that was taking shape in Israel, though in essence they followed the same working method as Albright and the others: the Bible in one hand, a spade in the other.

I wish these guys were still living so they would not let us brilliant moderns get away with such reductionist slander. We have built on their shoulders, and now we are so much better.

The minimalist view is summarized briefly:

According to the minimalists, the United Monarchy never split into two kingdoms, Judah and Israel, because it never existed in united form in the first place. Their account is that the two kingdoms developed side by side, with the Kingdom of Judah and its capital, Jerusalem, developing at a far later stage, after the consolidation of the Kingdom of Israel in the ninth and eighth centuries BCE. In this interpretation, David and Solomon are entirely fictional figures.

It is beyond my comprehension that anyone can believe this. It is to me an illustration of how little evidence matters in formulating conclusions.

The biblical account (with a completely different story than the minimalist view) has to come from somewhere. Finkelstein explains:

“Thanks to the writing skill, the potent theology and the creative outburst, this was the narrative that became dominant.”

The whole minimalist viewpoint comes down to this: the writers of the Bible were brilliant liars.

Perhaps we are seeing in them too much of a mirror of ourselves.

Garfinkel on identifying Qeiyafa as a Judahite site:

Garfinkel notes that other findings by him and his team, which are being made public here for the first time, also support the thesis that the city was part of the Davidic kingdom.

Instead of quoting a long section, what Garfinkel reveals here is the discovery of a cultic altar, the lack of any icons, and the lack of pig bones. This is important evidence.

Nadav Na’aman rejects Garfinkel’s argument about pig bones:

“Not one of the finds cited by Garfinkel links Khirbet Qeiyafa to a center in Jerusalem or even to the hill region. Both the longtime inhabitants of the land and the inhabitants of the hill region in the first Iron Age refrained from eating meat, undoubtedly as a reaction to Philistines’ eating habits.”

There are several things in this quotation that are problematic. Is he saying that the Canaanites didn’t eat meat? What is the relationship of the Canaanites and the Philistines who arrived only in 1175?

What evidence do we have that people reacted negatively towards Philistine eating habits?

Na’aman makes a very good point:

“The fact that someone puts forward the same argument time and again and accustoms the listeners to the ‘facts’ he voices does not consolidate the ‘facts’ that are being voiced,” Na’aman says. “We have to wait for the publication of the finds from the site and then consider its affiliation level-headedly.”

This, of course, applies to both sides.

Finkelstein on the “two gates” that Garfinkel claims to have found at Qeiyafa:

He is particularly impatient with claims about the existence of two gates and the name that was ostensibly given the city in their wake. “There are not two gates there,” he asserts. “There is one gate, the western gate. Ninety percent of what you see in the southern gate is a reconstruction. I intend to publish a photograph from the end of the dig and a photograph taken after the reconstruction, and every sensible person will see that there was no gate there.”

I have had the same questions myself, but I don’t remember seeing them in print. I confess that my suspicions were not diminished when Garfinkel hastily “reconstructed” the second “gate” in the middle of winter, very soon after the discovery. Why the rush? If Finkelstein is right, Garfinkel’s permit should be revoked.

Garfinkel should consider his own words:

“Qeiyafa is like a bone in the craw of all the minimalists,” he says. “This city exists, how do you explain it? Gradually there will be more and more sites from this period.”

In other words, Garfinkel should quietly do his work and let the accumulation of evidence convince scholars and the public. Qeiyafa alone will not “win the battle” for maximalists. The scholarly consensus of the next generation will come from the results of the present excavations of nearby Gezer, Gath, Tell Burna, and Tell Zayit.

If you read to the end of the article, you will find reference to a row about Socoh published only in the Hebrew press to date (but summarized on this blog previously).

Goren was granted the permit last month, but the episode itself swelled beyond its natural dimensions as a disagreement over an excavation permit. Prof. Lipschits says that Garfinkel breached the regulations by starting to dig at the site before receiving a permit. He sent his complaint to Dr. Gideon Avni, the head of the excavations and surveys unit of the Antiquities Authority, who rejected it.

I skipped a lot. Read the whole article for more provocative quotes and observations.

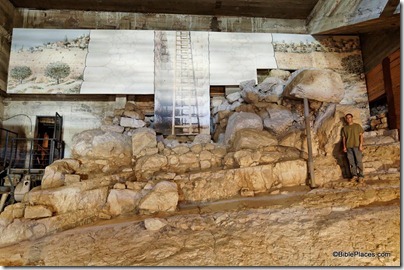

Elah Valley, aerial view from west