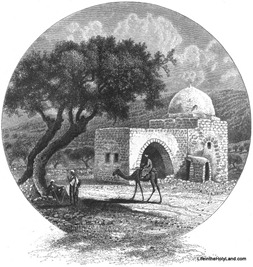

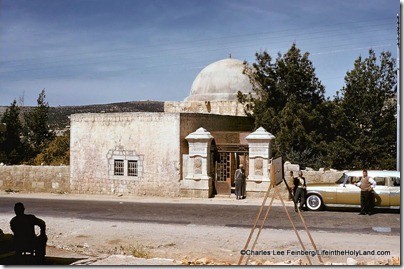

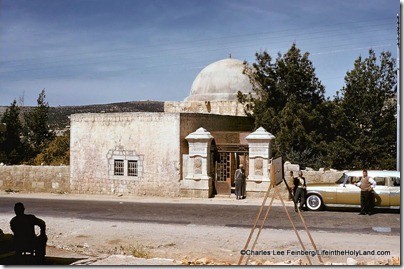

UNESCO’s designation last week of “Rachel’s Tomb” as a mosque was received with great criticism, including a pointed response by Israel’s prime minister. My interest is not in the identification of the domed structure in recent centuries. I’m willing to grant that “Rachel’s Tomb” is as Jewish as the Tomb of David on Mount Zion or the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. For many Jewish worshippers, that is enough. The site has been sanctified by the prayers of the faithful for centuries. I have no interest in addressing the issue of the late tradition, and thus this post is not really relevant to the UNESCO debate. The evidence for the site being a Muslim holy place in the last thousand years will not be evaluated here.

My interest is in whether Rachel, the beloved wife of Jacob, was buried anywhere near the location of the contested dome. The best evidence for answering this question is the oldest evidence, and the biblical data answers with a decisive “no.” Rachel was buried somewhere else.

The story of Rachel’s burial is related in Genesis 35:19-20, “So Rachel died, and she was buried on the way to Ephrath (that is, Bethlehem), and Jacob set up a pillar over her tomb. It is the pillar of Rachel’s tomb, which is there to this day” (cf. Gen 48:7). This verse seems to establish the matter, and if the investigation is halted at this point, the traditional location appears to face no objection.

The situation is more complicated than that, however. Shortly before the time of King David, the prophet Samuel anointed Saul and instructed him to “meet two men by Rachel’s tomb in the territory of Benjamin at Zelzah” (1 Sam 10:2). This verse appears to locate the matriarch’s burial place in the land allotted to the tribe of Benjamin. The detailed boundary descriptions given in Joshua 18 place Jerusalem on the southern boundary of Benjamin (18:16). Bethlehem of Judah, however, is about five miles (8 km) south of Jerusalem. If this was all the evidence we had, we might conclude that there is an obvious contradiction and one statement is right and the other is wrong. We might surmise that this is the result of competing ancient traditions. If that is the case, then the traditional site has no more than a 50% chance of being the actual location.

Closer examination, however, reveals that there is no contradiction but that both references are to the same place. The first piece of evidence is the existence of another Israelite town called Bethlehem.

Most people are aware of the Bethlehem of Galilee mentioned in Joshua 19:15. But there is yet another town with the same name in a city list in Nehemiah 7:26. In the midst of a series of sites clearly within the tribal territory of Benjamin, there is a place called Bethlehem. The existence of a Bethlehem in Galilee and a Bethlehem in Benjamin makes more understandable the frequent reference to “Bethlehem in Judah.” David was not from “Bethlehem,” but from “Bethlehem in Judah” (1 Sam 17:12; cf. Judg 17:7-9; 19:1-2, 18; Micah 5:2). It is noteworthy that Rachel’s tomb is never identified as being in “Bethlehem of Judah.”

In fact, Jeremiah corroborates the Benjamite location when he writes, “A voice is heard in Ramah, lamentation and bitter weeping. Rachel is weeping for her children” (Jer 31:15). Ramah is a well-known city in Benjamin, and it was apparently within earshot of Rachel’s tomb. Some might object that the Gospel writer Matthew seems to locate Rachel’s tomb near Bethlehem of Judah when he quotes this verse from Jeremiah (Matt 2:16-18). But Matthew makes no such identification, and the fulfillment that he sees lies not in geography but in history. The exile begun in Jeremiah’s day continues in the days of Jesus as foreign rulers continue to slaughter the Jewish children.

There is yet one more potential objection that remains before the Bethlehem of Judah can be completely dismissed from consideration as Rachel’s burial place. The Genesis account says that Rachel was buried “on the way to Ephrath (that is, Bethlehem).” It is well known that the prophet Micah predicts that the Messiah would come from “Bethlehem Ephrathah,” a place in Judah (Mic 5:2; cf. Ruth 1:2). If this is the same place as where Rachel was buried, then there is simply no way to resolve the conflicting evidence. But the “Ephrath” of Genesis could well be a reference to the Benjamite site of “Parah” in Joshua 18:23 (though these words look significantly different in English, they are very similar in Hebrew). The prophet Jeremiah describes going to “Parat” to hide a belt, and it is reasonable that this is the site in Benjamin not far from Jeremiah’s hometown of Anathoth (Jer 13:4-7). (Some versions translate this as the “Euphrates” River, but it seems unlikely that Jeremiah would travel not once but twice on this extremely long journey for a very simple object lesson.) Until today a spring known as Parat exists in the territory of Benjamin not far from Jerusalem.

Additional support for a location in Benjamin is found in Genesis 35:21, which says that after Rachel was buried, Jacob traveled on to “Migdal Eder.” This location is identified in Micah 4:8 and m. Seqal. 7:4 as a place near Jerusalem. This further supports the location of Rachel’s tomb as north of Jerusalem and within the territory of Benjamin.

The evidence can be summed as follows: all the biblical evidence conforms with a Benjamite location for Rachel’s tomb. That there was a Bethlehem in Benjamin as well as a Parat/Ephrath in Benjamin is certain. This location was well known in Saul’s time, and it was the basis for a prophecy by Jeremiah.

The mother of Benjamin was buried in the same territory that would later be deeded to the descendants of the son to whom she died giving birth.

There is yet another piece of extrabiblical evidence that cannot be said to prove the point, but it

certainly is a curious “coincidence.” Very close to the Parat spring there are a series of large stone monuments. These monuments are located directly on a north-south road that served the ancients traveling through Benjamin on their way to the lush watering hole of Parat. The site is east of Ramah by a few miles, and an Israeli military official has told me of acoustical experiments that he performed with his soldiers that demonstrated that it was within hearing distance of Ramah. A local Arab tradition, first recorded by Western explorers in the 19th century, identified these monumental structures as Kubr Benei Israel, the “tombs of the sons of Israel.” Whether these structures date to the time of Rachel has not yet been determined by archaeological means, but the biblical evidence suggests that her tomb is likely in this same area.

How did the traditional location near Bethlehem of Judah arise? This is very easy to understand.

Early pilgrims knew of only this Bethlehem and they were unaware of the other biblical evidence.

They established the site at a location convenient for visiting tourists. Not far from here they built a

church where they said Elijah rested on his flight from Jezebel and another church where they claimed that Mary fed Jesus and a drop of milk fell to the ground. The same sort of logic was used for locating the tomb of David on what they thought was “Mount Zion.” Byzantine and post-Byzantine traditions sometimes accord with the biblical evidence, but they fall short in the case of Rachel’s tomb.

It is unlikely that any of the ideas presented here are original to me. You can pursue the subject further in the following resources (asterisks indicate most helpful works).

Beck, Astrid Billes. “Rachel (Person).” In Anchor Bible Dictionary. Volume 5, 605-7. D. N. Freedman, ed. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

*Clermont-Ganneau, Charles. Archaeological Researches in Palestine during the Years 1873-74, vol. II. London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1896. Reprint, Jerusalem: Raritas, 1971, p. 278-79.

*Hareuveni, Nogah. Desert and Shepherd in Our Biblical Heritage. Trans. H. Frenkley. Tel Aviv: Neot Kedumim, 1991, pp. 64-71.

Jung, K. G. “Rachel’s Tomb.” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Volume 4, 32. Geoffrey W. Bromiley et al, eds. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1988.

*Luker, Lamontte M. “Rachel’s Tomb (Place).” In Anchor Bible Dictionary. Volume 5, 608-9. D. N. Freedman, ed. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

Rainey, Anson F. and R. Steven Notley. The Sacred Bridge. Jerusalem: Carta, 2006, p. 145.

Thompson, Henry O. “Ephraim (Place).” In Anchor Bible Dictionary. Volume 2, 555-56. D. N. Freedman, ed. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

For another perspective, see Leen Ritmeyer’s post and my comments there.