I’ve often been asked how tells grew so tall. True, winds in the Middle East blow lots of dust throughout the year, but that certainly cannot account for tells which are 80 feet high. A.D. Riddle recently sent me the following quotation from C. Leonard Woolley, in which he gives a good explanation for the phenomenon of tells from his report on excavations at Carchemish. I have placed in bold the answer to this question, but the whole is worth reading, despite its length. Woolley writes:

The whole of North Syria is dotted with tells, artificial mounds which consist of and conceal old settlements. So little has been done in the way of excavating these mounds that it is dangerous to theorize too much about the nature of what lies beneath them; but certain features which are common to all, or which distinguish one from another, may, with such more sure information as digging has afforded, serve to throw light on the conditions of life which brought them into being and shaped their history.

The neolithic folk, the original founders, undoubtedly, of all these tells, built their huts of mud and rubble either on some slight knoll or, where none such lay to hand, on an artificial platform laboriously piled up with basketful after basketful of earth,—piled just high enough to raise them above the damp of the level soil. The huts fell in ruins, and these ruins raised the ground level on which new homes were built, and that at a goodly rate, for mud-brick walls tend to be thick, and their cubic contents are very great in proportion to the area they enclose, and as the bricks can scarcely be used a second time the whole material of the fallen house was let lie where it fell and was merely leveled for the foundations of the new. Year after year went on this accumulation of débris and of house rubbish (there are sites in the Near East where the rubbish-heaps outside the walls are nearly as extensive as and much higher than the ruins themselves), and the original platform reached a height at which it commanded all the surrounding country. Then a wealthier generation, perhaps more warlike, or more timorous, walled the hill-top round, turning their village in to a stronghold. The chance of an asylum would attract new-comers, whose houses huddled together on the slopes of the mound and spread over the low ground at its foot, and this in its turn began to heap itself up above the level of the plain around. After a while the outsiders, too, might demand protection for their homes, not content to leave them in war-time to the mercy of the enemy while themselves taking refuge in the fort: they built a wall round the new outer town. In proportion as the whole town was thus made defensible, the original settlement, the tell, tended to become less a place of general residence, more and more the centre of administration and of worship; here the princeling might live in isolated state, here were the barracks of his regular retinue, here the temples which from of old had been the houses of gods or heroes deified. At the same time the defences of the tell were kept in good repair, for whatever might be its use of every day, it was still the inner stronghold, the last resort in case the rest should fall; from a military point of view the outer town and its high citadel within might be compared to the mediaeval castle with its bailey and its keep.

Of course tells differ one from another in form as they differed in their history. There are low mounds scarcely noticeable above the level of the plain, short-lived villages whose ruins, scanty at their best, may have grown even less distinct through the gradual raising of the ground about them-the natural effect of long cultivation and often too of the ploughing of the nearer hillsides, whence little by little the rain carries the loosened surface soil down to the valleys. There are small steep-sided cones which, one thinks, can hardly be other than keeps or watchtowers, not the outgrowth of village settlements but military foundations to secure frontiers or trade-routes. There are rather larger whale-backed mounds, higher and more abrupt at one end and tailing off fanwise at the other, where one can almost see the cluster of domed or flat-roofed single-storied mud huts with, at the outskirts, the effendi’s two-storied house of stone dominating them from its higher ground. Again, on a larger scale, we have the steep-sided C-shaped tell with a broad channel running down it at a gentler slope between the horns of the letter, like a volcano’s crater with a gap in the rim; it looks as if, on the older mound’s flat top, a huge ring wall had been built with a gateway and an approach thereto between flanking towers. In other cases the main tell is more or less pyramidal in form with, on one side, the lower rounded mound of the outer town, its flimsier walls indistinguishable now from the heaped mass of house ruins which they enclose: in a few, the outer walls stand out clearly as a ring of earthworks overtopped only by the great bulk of the acropolis within.

Source: Woolley, C. Leonard. 1921. Carchemish: Report on the Excavations at Jerablus on behalf of the British Museum, Part 2: The Town Defences. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

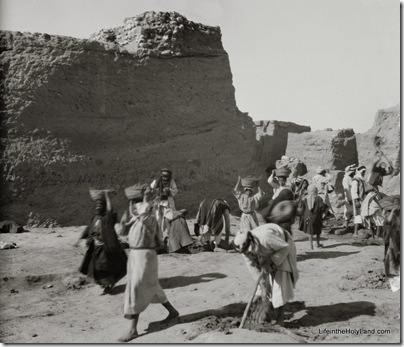

The two photographs are from the newly published Southern Palestine volume of The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection (originally Library of Congress, LC-matpc-13993 and LC-matpc-13986).