Last week I linked to Bryant Wood’s article on new evidence for Israel’s existence in 1400 BC.

According to three European scholars, an inscription mentions Israel several hundred years earlier than the Merneptah Stele.

There are several ways to respond to this proposal. James Hoffmeier, an advocate of the late-date exodus (1230 BC), says that the inscription should not be read as Israel and thus is irrelevant to the question of the exodus.

In an article published in the January/February 2012 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review (HT: G. M. Grena and Shmuel Browns), Hershel Shanks summarizes the recent studies and concludes with a discussion about multiple departures from Egypt by Israelite tribes at different times. Earlier advocates of such include Albrecht Alt, Yohanan Aharoni, and Abraham Malamat.

Such an approach is wrong-headed, I believe. In the first place, it can only be reconciled with the biblical account by considering the latter to be only an elaborate and glorious myth created hundreds of years later (and peppered liberally with shameful acts of those who devised the myth). Second, such an approach replaces one exodus for which there is no record in Egyptian sources with many exoduses for which there are no record in Egyptian sources.

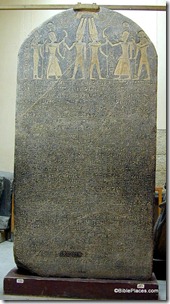

A better approach is to take a step back and reconsider the issue afresh. The reason why scholars argued for a 13th century BC date for the exodus/conquest in the first place was because of an apparent lack of evidence for Israel in Canaan at an earlier time. The Merneptah Stele, paired with the appearance of hundreds of agricultural villages in the 12th century, has been considered to provide evidence for the earliest Israelites. This evidence does not, however, tell us anything about Israel’s entrance into the land. It tells us only when Israel was already in the land (and defeated by Egypt).

Last year I showed how the Merneptah Stele gives evidence for Israel’s invisible (to archaeologists) presence in the land of Canaan for some time before they settled down in the hill country villages.

The recently published inscription, if the reading of Israel is accurate, provides even earlier evidence for the nation’s existence. As with the Merneptah Stele it does not tell us anything about the exodus or the conquest. To theorize that there were multiple exoduses when these inscriptions provide evidence for none is the wrong course indeed.

The best historical reconstruction takes into account all of the evidence. Israel fled from Egypt in about 1450 BC. They arrived in Israel in about 1400 BC. They continued their pastoral way of life that they were used to from the time of the patriarchs, their time in Egypt, and their time in the wilderness. This lifestyle left relatively little discernible and distinctive archaeological evidence from 1400-1200 BC. Some factors (weather?, political turmoil?, invasions?) forced the Israelite tribes to settle down at the beginning of what archaeologists call the Iron Age. This corresponds well with the record in the book of Judges in which the first indication of a settled existence is mentioned in the time of Gideon, who led the nation in about 1200.