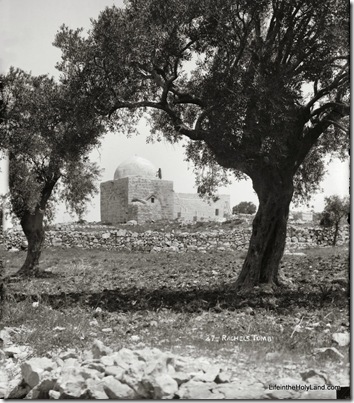

A friend wrote and asked me if I knew why the star in the Bethlehem church has 14 points. This star is located at the traditional place of Mary’s delivery of Jesus in a cave below the Church of the Nativity.

Traditional place of Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem

Traditional place of Jesus’ birth in BethlehemI don’t know. Everyone knows there were three magi, not fourteen. Maybe there were fourteen shepherds? Or maybe fourteen cows (or combination of stable animals)? Or fourteen rooms in the inn? Maybe Jesus was born on the 14th, and not the 25th of December. Maybe, like Joseph in Genesis, it stood for twelve children and his mother and father.

There’s a list on this web page that shows stars with various numbers of points and gives their explanations. The four-pointed star is used as the “star of Bethlehem,” and its shape as a cross is symbolic of Jesus’ death. The five-pointed star is also the “star of Bethlehem,” as it is “shaped roughly like a human being.” There’s the six, seven, eight, nine, and twelve-pointed stars. But none with fourteen.

I asked my friend Tom Powers in Jerusalem. He wondered if it might be related to the 14 Stations of the Cross. But then he checked with a friend, who suggested it stands for the three-fold “fourteen generations” of Jesus’ genealogy given in the Gospel of Matthew. He and I agree that makes the best sense, though we haven’t seen it in print.

A few comments on those genealogies now that I’m thinking about them. The genealogy of Jesus in Matthew has three sections with fourteen generations each. The place where the breaks are located is significant. The first break is with David. Matthew’s Gospel makes the point that Jesus is the “Son of David,” the expected Messiah described in the Old Testament. The second break is at the exile. A more subtle point that Matthew makes is that Jesus is the expected child who would be born in the exile to bring his people out of the exile. You really have to understand Isaiah in order to get this, and Matthew did.

The fourteen generations are not exhaustive. They appear to be arranged that way (with certain known individuals left out) in part to assist in memory. I wonder if you’ve ever taken advantage of this help that Matthew provided. If that’s not enough, you might find the song, “Matthew’s Begats,” by Andrew Peterson helpful. The entire song is composed of this genealogy. This Christmas season I’m enjoying not only this song, but the entire album. The best Christmas music is drenched with the Old Testament.