(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

It is impossible to send a photographer back to biblical times to capture the sights that were familiar to Abraham, David, and Peter…but a photographer taking pictures in the early 20th century could come pretty close.

Our picture of the week comes from Volume 1 of The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection. This is a remarkable collection of photographs from the first half of the 20th century. I had a hand in the early stages of this project, working through and cataloging thousands of photos. It was a remarkable experience and in the process I learned much about the cultures of that period, the daily life of the inhabitants, the notable events of the day, and the various archaeological sites. The collection published by LifeInTheHolyLand.com is a selection of the best of the photographs taken by the American Colony and Eric Matson. Over 4,000 photos from Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt are presented in eight volumes. We will spend the next few weeks highlighting a photo from each volume. LifeInTheHolyLand.com describes the collection in this way:

Founded in 1881 by Horatio Spafford (author of the famous hymn, It is Well With My Soul), the American Colony in Jerusalem operated a thriving photographic enterprise for almost four decades. Their images document the land and its people, with a special emphasis on biblical and archaeological sites, inspirational scenes, and historic events. One of the photographers, G. Eric Matson, inherited the archive, adding to it his own later work through the “Matson Photo Service.”

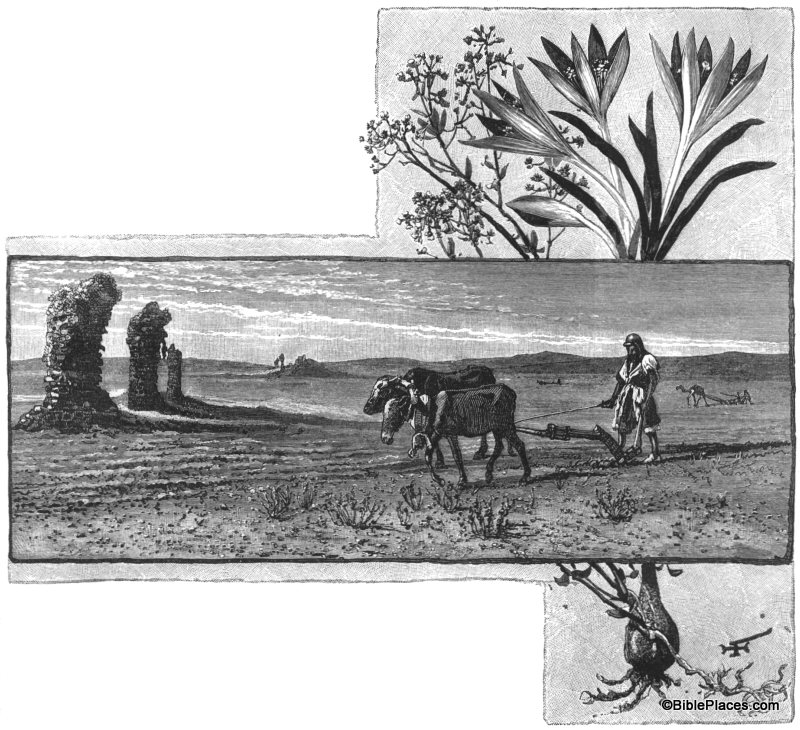

As you spend time in the collection, you really do feel like you have stepped back in time. The landscapes are picturesque because buildings are sparse or non-existent and the air is free from smog. The local villages are full of primitive dwellings while the new churches, hospitals, and municipal buildings are pristine. You see dirt roads, horse-drawn carriages, boats powered by wind, and people walking from one town to the next. Archaeological sites are untouched by the excavator’s spade or are being subjected to excavation for first time. What an amazing time to be a photographer in the land of the Bible!

For example, as I was looking through Volume 1 the picture above stood out to me. Two women are walking barefoot along a narrow, dirt path in the hills of Ephraim, balancing water jugs on their heads. Behind them is the small town of Lower Beth Horon surrounded by farmland and a handful of trees. You can almost feel the silence that must have hung in the air in this sleepy countryside. Such a scene must have been familiar during the biblical period, and a photo such as this has the ability to transport us back to biblical times and to help us read Scripture in its historical context.

This photograph and 600 others are available in Volume 1 of The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection and can be purchased here for $20 (with free shipping). Volume 1 focuses on “Northern Palestine,” and other photos from the volume can be seen here, here, and elsewhere on LifeInTheHolyLand.com. Images and information about other work carried out by women during this period can be found here.